Lanternflies on the move: Spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula

Slender spotted lanternflies like this one that landed on a small twig just before I snapped this photo are often flight capable, unmated females searching for suitable host plants on which to feed and produce batches of eggs.

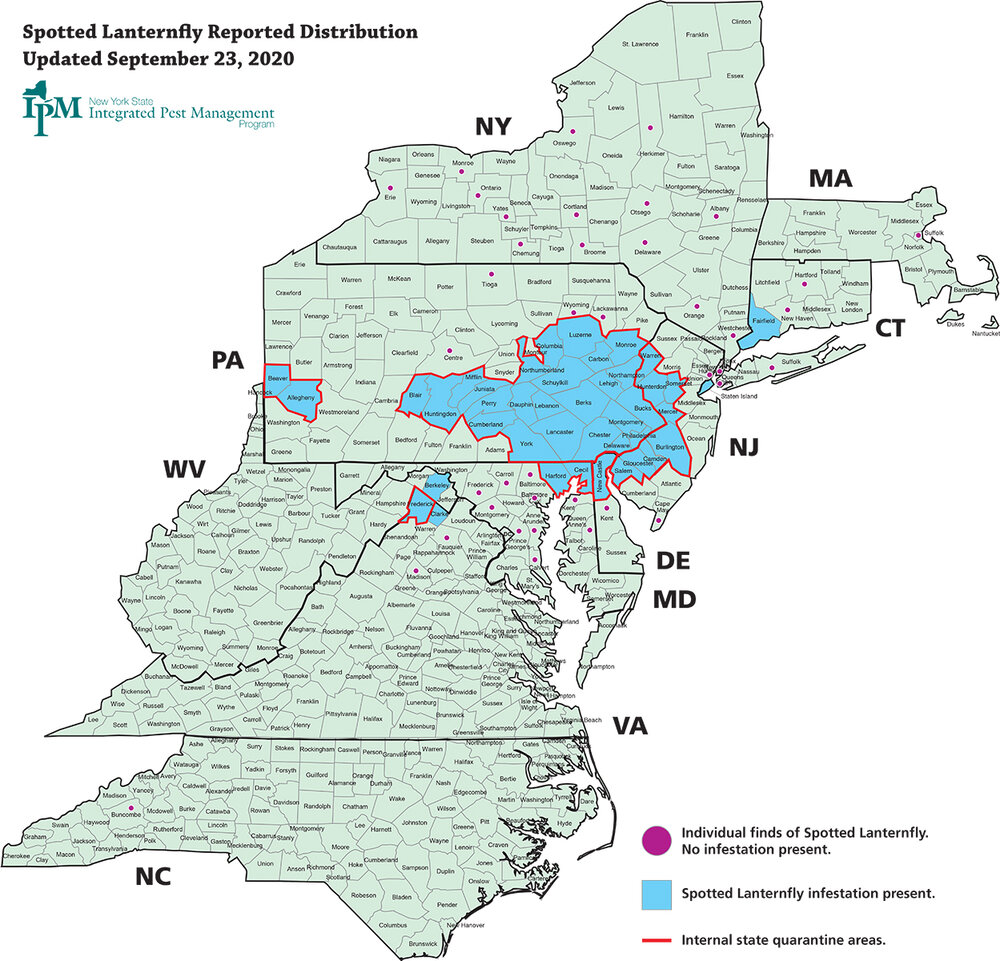

Last week while driving from Maryland to New Jersey along Route 30 in southeastern Pennsylvania, I stopped for a bite to eat in scenic Rohrerstown. This once forested town settled by the Pennsylvania Dutch now finds itself the home of a new six-legged settler from Asia, the spotted lanternfly. We met the spotted lanternfly in previous episodes of Bug of the Week where we learned about its discovery in Berks County in 2014, how it moved to locations nearby, and what citizens could do help local officials track its movement and slow the spread of this killer of vineyards.

In deciduous forests spotted lanternfly nymphs traveled surprisingly long distances, up to 65 meters from a point of release.

Lanternfly adults and their youngsters, called nymphs, remove large quantities of phloem sap from woody plants as they feed. The excess is excreted from their rear end in copious amounts as a sugary waste product called honeydew. More than 103 plant taxa of woody and herbaceous plants serve as hosts for spotted lanternflies. Spotted lanternflies can be severe pests of fruit and shade trees, grapes, and hops. Massive infestations in vineyards have withstood repeated applications of insecticides and still caused the demise of entire vineyards. In home landscapes, hundreds of these rascals have been observed feeding on a single plant, where they rain scads of honeydew onto vegetation and the earth below. As with honeydew produced by other phloem feeders such as soft scales and aphids, the honeydew excreted by lanternflies fouls foliage, fruit, and underlying plants, and serves as a substrate for the growth of a fungus known as sooty mold. Honeydew makes leaves sticky and fruit unmarketable, and sooty mold further disfigures leaves and fruit and may impair photosynthesis. This presents a huge economic problem for growers of apples, cherries, peaches, and grapes. Sweet honeydew and its fermentation products also attract a variety of stinging insects like yellow jackets and paper wasps. In addition to excreting honeydew, lanternflies may be so numerous that they cause wilting and dieback of branches.

While I munched a panini at an outdoor table, I was astonished to see airborne spotted lanternflies crashing into plate glass windows of nearby buildings. The nearest trees that might have spawned these aeronauts were several hundred yards away. Earthbound lanternflies dashed across sidewalks and streets and hapless lanternflies met untimely death beneath the feet of pedestrians and wheels of cars. Amidst a concrete jungle, I wondered where these buggers had come from and how they got there. One somewhat harebrained possibility was that they hiked as nymphs from egg masses laid on stones or Ailanthus trees bordering a distant hedgerow and spent their youth sucking sap on one of a dozen red maples struggling to survive in small concrete coffins in the center of the parking lot. A clever study conducted by Kelli Hoover and her colleagues at Penn State found that some spotted lanternfly nymphs travel as much as 213 feet in their quest to find a suitable host, but only about half would travel 56 feet. While this pretty much ruled out a hike from the hedgerow, a quick check of the maple trees confirmed no signs of occupation by lanternflies and infirmed my nymphs-take-a-hike hypothesis. More likely, of course, is that these travelers developed on distant trees and were on their way somewhere else.

On a sunny late summer afternoon in a restaurant park in scenic Rohrerstown, PA, spotted lanternflies were on the wing. They crashed into windows, wandered on sidewalks, and met gruesome ends beneath human feet and tires of vehicles. Wanderers displayed their impressive jumping skills when harassed by a giant finger and one contemplated a trip to New Jersey on the rear bumper of my car.

Rotund spotted lanternflies like this one with a bright yellow underbelly are generally mated females with limited flight ability.

In addition to being capable flyers, I learned that they were excellent jumpers as well, much to the amusement of fellow diners watching my feeble attempts to capture the earthbound insects. When I finally snagged a couple I found them to be rather trim, unlike rotund lanternflies I had discovered on the trunks of trees in the latter weeks of autumn in previous years. Recent studies by scientists in Pennsylvania reveal some of the secrets to the autumnal movements of adult spotted lanternflies. Thomas Baker and his colleagues at Penn State discovered that these slim fancy flyers are primarily unmated females capable of flights ranging from roughly 30 to 150 feet. Their spontaneous flights are believed to be quests to find suitable hosts, plants that will supply sufficient nutrients for them to fatten up and deposit a complete complement of eggs before cold weather puts an end to their mischief. The Penn State team also assessed the flight worthiness of plump yellow-bellied lanternflies. A vast majority of these heavy females had successfully mated but their ability to fly was weak and limited to only about 12 feet when launched into the air.

Spotted lanternfly egg masses are rather nondescript and often deposited in natural and human-made objects including masonry products, lawn furniture, pallets, and vehicles including automobiles and railroad cars. Movement of eggs is thought to be a major component of the long distance spread of spotted lanternflies.

While autumnal spontaneous flights have been witnessed on a regular basis, these relatively short distance flights of hundreds of feet likely account for only a minor component of the spotted lanternflies’ spread to adjacent counties and states. From their initial discovery point in Berks County in 2014, isolated spotted lanternflies have been recovered in eastern Massachusetts some 270 miles distant and in Buncombe County, North Carolina almost 500 miles away. According to entomologist Julie Urban, also at Penn State, the most likely explanation for these long distance peregrinations lies in human-assisted transport of lanternfly eggs. It is believed that spotted lanternflies arrived in Pennsylvania around 2012 from Asia in a shipment of stone products bearing lanternfly eggs, a trip of some 7,000 miles. Unlike many herbivorous insects that lay eggs on food plants for their young, spotted lanternfly mothers deposit egg masses on non-host objects including stones, cinder blocks, lawn furniture, and vehicles, in addition to trees. These nondescript masses of eggs are easily overlooked on natural and human-made items and easily transported inadvertently by road or rail. Unfortunately, at the epicenter of the spotted lanternfly infestation in southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey, several major interstate highways and railways run north and south, east and west, crisscrossing a region replete with warehouses, truck stops, and railroad depots embedded in a matrix of orchards, vineyards, and forests that serve as hosts for lanternflies.

This map shows the current locations of established infestations of spotted lanternflies (blue counties), internal state quarantines are outlined in red, and counties with isolated detections have a small purple dot. Map courtesy of Brian Eshenaur and the New York State Integrated Pest Management Program of Cornell University.

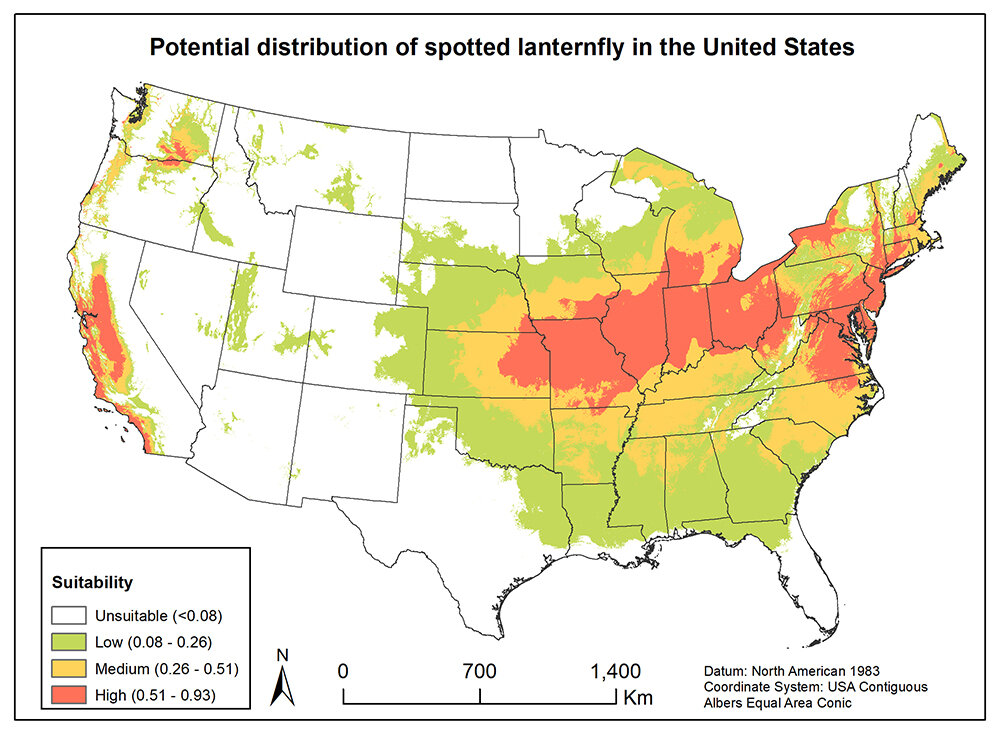

So, how far will spotted lanternfly spread in the US? Based on recent climatic data from the US and Asia, scientists suggest that much of the mid-Atlantic and Central regions of the US and portions of California, Oregon, and Washington State have climates suitable for the survival of spotted lanternfly. In addition to well-established infestations in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Delaware, New Jersey, West Virginia, and Maryland, isolated living or dead individuals have been found in more than three dozen locations in the previously listed states and also in New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. As I finished my lunch and headed back to my car, I noticed a skinny spotted lanternfly perched on my rear bumper ready to hit the road with me to the Garden State. As I constructed this tale last week, I received an update that several living spotted lanternfly adults had been spotted in Greenwich, Connecticut. So, if you travel in the aforementioned infested zones in autumn, when you stop for a biobreak, meal, or fuel, please give yourself and your vehicle a quick once over to be sure you are not transporting these clever hitchhikers. Will spotted lanternflies soon be coming to your neighborhood? Time will tell, but as I have often heard said, you can usually bet on the bug. (BTW, of course I removed the lanternfly from the bumper of my car and inspected it for other hitchhikers before I drove away.)

This map shows the potential distribution of spotted lanternfly in the United States based on climatological data. Areas with the highest probability of supporting lanternflies appear in dark orange and areas unsuitable for lanternflies are white. Map courtesy of the Entomological Society of America at Entomology Today, October 3, 2019.

To learn more about spotted lanternfly please visit the brilliant, fact-packed Penn State Cooperative Extension Website at this link: https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly

To watch a video of spotted lanternflies in flight, please click this link.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Dr. Shrewsbury for spotting and wrangling spotted lanternflies for this episode. We acknowledge the great work of scientists contributing to our knowledge of this pest, with particular thanks to authors of articles used as references including “Worldwide Feeding Host Plants of Spotted Lanternfly, With Significant Additions from North America” by Lawrence Barringer and Claire M. Ciafré, “Perspective: shedding light on spotted on lanternfly impacts in the USA” by Julie M. Urban, “Dispersal of Lycorma delicatula (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) Nymphs Through Contiguous, Deciduous Forest” by Joseph A. Keller, Anne E. Johnson, Osariyekemwen Uyi, Sarah Wurzbacher, David Long, and Kelli Hoover, and “The Establishment Risk of Lycorma delicatula (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) in the United States and Globally” by Tewodros T. Wakie, Lisa G. Neven, Wee L. Yee, and Zhaozhi Lu. Thanks to Brian Eshenaur and the entire team at the New York State Integrated Pest Management Program of Cornell University for providing the updated maps of spotted lanternfly in the US and to the Entomological Society of America for providing the map of the potential distribution of spotted lanternfly in the US.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week