‘Twas the week before Christmas and what did I spy: The silverleaf whitefly, Bemisia tabaci

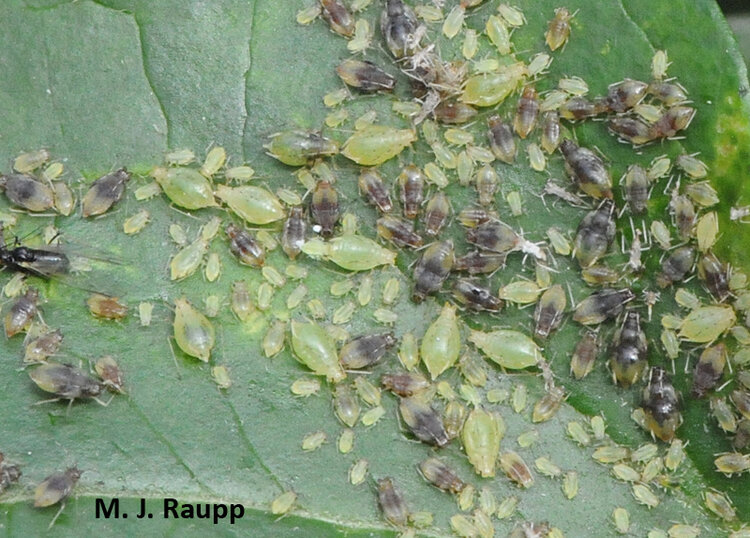

And what to my wondering eyes should appear, but a colony of whiteflies, bringing holiday cheer.

One of the real delights of the holiday season is adding festive plants to the home décor. As we have seen in previous episodes of Bug of the Week, this often means that some six and eight-legged creatures including mantises, adelgids, and spiders sometimes accompany a Christmas tree when it arrives indoors. These plant-related holiday surprises are not limited to Christmas trees, oh no. This week, let’s visit another fascinating but dastardly insect that sometimes makes its presence known on one of my favorite holiday plants, poinsettia. Decorating the home with poinsettias is a holiday tradition that likely originated in Mexico, where poinsettias add beauty to holiday nativity crèches. According to legend, in the town of Cuernavaca a young girl had no flowers to adorn the nativity at her church. Instead, she collected a weed growing by the roadside. An angel transformed the weed into the beautiful poinsettia, and ever since, poinsettias have been used as a seasonal decoration. Poinsettias are as much of a holiday tradition as mistletoe, holly, and an evergreen tree in many homes.

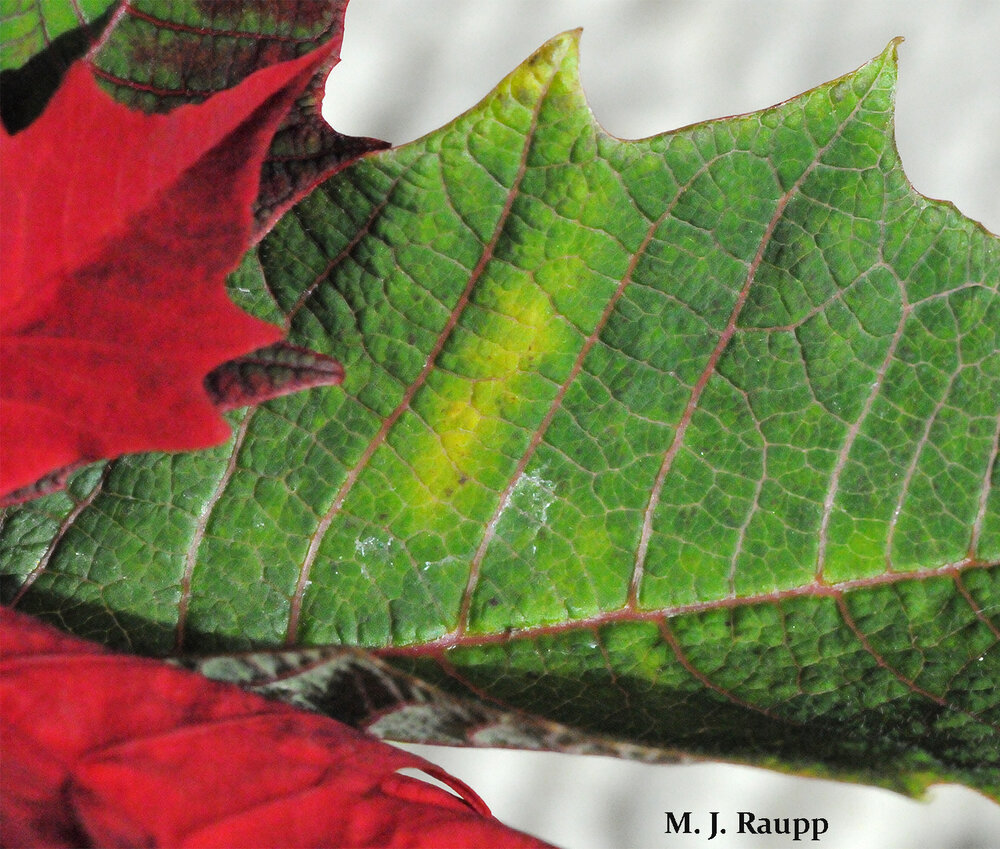

Yellow patches on poinsettia leaves may be a sign of whiteflies feeding below.

As I browse displays of poinsettias that have sprung up in every hardware and grocery store, I’m on the lookout not just for holiday decorations, but for holiday whiteflies. Whiteflies are small sucking insects and relatives of more commonly known sap-suckers such as beech and woolly alder aphids we met in recent previous episodes. To spot a whitefly-infested poinsettia, first look at the color of the plant’s leaves – not the red, yellow, or speckled bracts comprising the blossom. The leaves on most varieties should be a clear deep green with no evidence of yellow patches or streaks. Leaves with yellow patches that are undersized, twisted, puckered, or curled can be the ghost of holiday problems yet to come. Whiteflies are usually found on the underside of leaves where they insert tiny beaks into the plant’s vascular system to extract sugar-rich sap from a vascular element called phloem. Plant sap contains nutrients needed for their growth and development. Large populations of whiteflies can cause leaves to drop prematurely. As whiteflies feed, they excrete a sugary waste product called honeydew. This sticky liquid can become a substrate for the growth of an ugly fungus known as sooty mold.

Whiteflies have four stages in their lives, egg, nymph, pupa, and adult. An adult female whitefly lays eggs on the undersurface of a leaf. After several days, eggs hatch and mobile nymphs, called crawlers, move about the leaf surface until they find a suitable place to feed. Nymphs hunker down, shed their skin, and become stationary for the remainder of their youth. After several molts, a pupa forms, and from this pupa emerges the adult whitefly. Shed pupal skins often festoon the undersides of leaves. Adult whiteflies look like tiny white moths. They too have sucking mouthparts and suck the sap of poinsettias. If disturbed, they flutter from the leaf surface. The nymphs and pupae are usually yellowish or whitish and translucent. Red eyespots can be seen on the pupa shortly before the adult whitefly emerges.

With wings yet to unfold, an adult whitefly emerges from its pupal case. A bit later with wings now fully expanded, polishing up the thorax and antennae is the next order of business to get ready for the holidays.

Droplets of sweet sticky honeydew are produced as a waste product when whiteflies feed.

For the folks that grow poinsettias, whiteflies can be a very serious problem. If populations become too great, entire crops are lost. The most common whiteflies that come home with poinsettias are the greenhouse whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum, and the silverleaf whitefly depicted in this Bug of the Week. A strain of silverleaf whitefly, the dastardly “Q biotype”, has been found in several states in the US. This strain is resistant to many of the pesticides formerly used to control whiteflies and causes headaches not only for the greenhouse industry but also for growers of some of our most important agricultural crops including tomato, peppers, squash, cucumber, beans, eggplant, watermelon, cabbage, potato, peanut, soybean, and cotton. Fortunately, entomologists are finding new ways to control whiteflies using tiny wasps that attack them, predatory beetles that eat them, and pathogens that give them lethal infections.

If this Bug of the Week sounds a bit like the Nightmare before Christmas, try not to panic. Don’t let a few whiteflies on your poinsettia spoil the holiday. A few whiteflies will not ransack your poinsettia between now and the New Year and, hey, many poinsettias will join other decomposing vegetation in the compost well before Valentine’s Day. However, if whiteflies are numerous and your poinsettia looks whipped, and you had planned to keep your poinsettia going with the other house plants, it may be best to toss it out and replace it with one not bearing tiny six-legged gifts. Many fine, pest-free poinsettias can still be had in retail markets large and small. So, Happy Holidays to poinsettias, whiteflies and all!

Acknowledgements

The University of Florida Extension publication “Sweetpotato Whitefly B Biotype, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae)”, by Heather J. McAuslane and Hugh A. Smith, was consulted in preparation for this episode of Bug of the Week. Carol Of The Bells by Audionautix is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Artist: http://audionautix.com/

Bug of the Week wishes everyone a joyous, happy, and safe holiday season.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week