Do Winter Temperatures Predict Pest Activity?

Some people love a cold, snowy winter, while others much prefer the milder temperatures we have seen in the Northeastern United States in recent years. Regardless of their preference, few people fail to consider how winter temperatures impact pest activity for the seasons that follow.

For many people, thinking about pests is typically limited to spring, summer, and fall — the months with peak pest activity across many species and regions. You may already be aware that the change of seasons usually brings a spike in insect and rodent sightings. However, you may be surprised to learn that winter temperatures can have other effects on pests and rodents that extend well into the year ahead.

What a Mild Winter Means for Rodent and Pest Activity in the Spring

Many rodents can’t survive long periods exposed to snow and cold. Additionally, mild winters can increase the survival rates of insects. As a result, the course of the winter season can cause a potential uptick in rodent or insect activity in spring months. Additionally, during warm stretches, insects may become more active and deplete their energy. This can cause them to die when cold snaps occur or leave them vulnerable before their typical host is available again for feeding.

Repeated freeze-thaw cycles can reduce insect survival. Adding to the problem, mild winters and overall warmer than normal temperatures can increase pests’ geographic range, leading to the spread of pests to new areas and increased activity.

Even if winter is snowy, many insects may survive if the temperatures aren’t too low. Snow can protect and insulate pests like ticks and mosquitoes in both egg and hibernating adult forms.

Mild winters also can increase rodent populations. For example, data shows that white-footed mice populations have increased throughout the Eastern United States due to warmer overall temperatures. Mice populations usually decline during harsh winters. However, mild winters allow more mice to survive, increasing the population size in spring.

How a Harsh Winter Impacts Rodents and Pests

Insects don’t regulate their body temperatures. Instead, their internal temperature depends on their environment. Once external temperatures dip below 50 degrees Fahrenheit, they can’t function or develop further. It isn’t until temperatures dip below – 4 degrees Fahrenheit that most insects freeze. For winter to kill off many populations, the season must feature prolonged, extreme cold. For a winter with shorter periods of cold, insects may survive with a reduction in their potential to reproduce, grow, and develop.

Cold, snowy winters typically send rodents scurrying indoors. Many mice and rats will seek shelter in homes, businesses, and other structures to stay warm and safe throughout the winter. Consequently, a cold winter often means increased winter rodent activity indoors. Snowy winters may produce a wet spring with greater growth of seeds and grasses. This provides rodents with more food and can increase rodent activity, something you may notice the following fall season, when rodents start heading indoors.

Signs of Rodent Activity

Rodents can create significant property damage and pose a serious health risk. Contact with saliva, urine, and droppings can spread disease-causing pathogens to humans and pets.

Some of the most common rodents that homeowners and businesses contend with are mice and rats. Signs of an infestation include droppings, chewed food items and wires, gnaw marks on walls, and scurrying sounds in ceilings and walls. It’s important to note that mice and rats aren’t the only rodents that can move indoors during winter. Squirrels, chipmunks, and other pests also pose a problem.

Squirrels

With their fluffy tails and often inquisitive expressions, squirrels can be fun to watch — when they’re outside. Indoors, squirrels can create extensive damage, chewing holes in the roofline and eaves, destroying siding, and nesting in insulation. Squirrels often gnaw wires, damage insulation, and leave droppings and urine everywhere they go.

Chipmunks

Chipmunks make a distinct chirping noise, which can alert you to their presence. Infestations may also be marked by gnawed seeds, nutshells, and other food scattered around the area. Other signs include scratching and scurrying in walls and ceilings, chew marks, and waste trails. Chipmunk droppings look similar to other rodents, which is like dark grains of rice.

Bats

Bats play a critical role in the ecosystem and typically nest while raising their young during spring and summer. That’s why careful removal according to local and federal protective regulations is critical. Signs of a bat infestation include scratching sounds at night, stained siding, and a strong smell of ammonia.

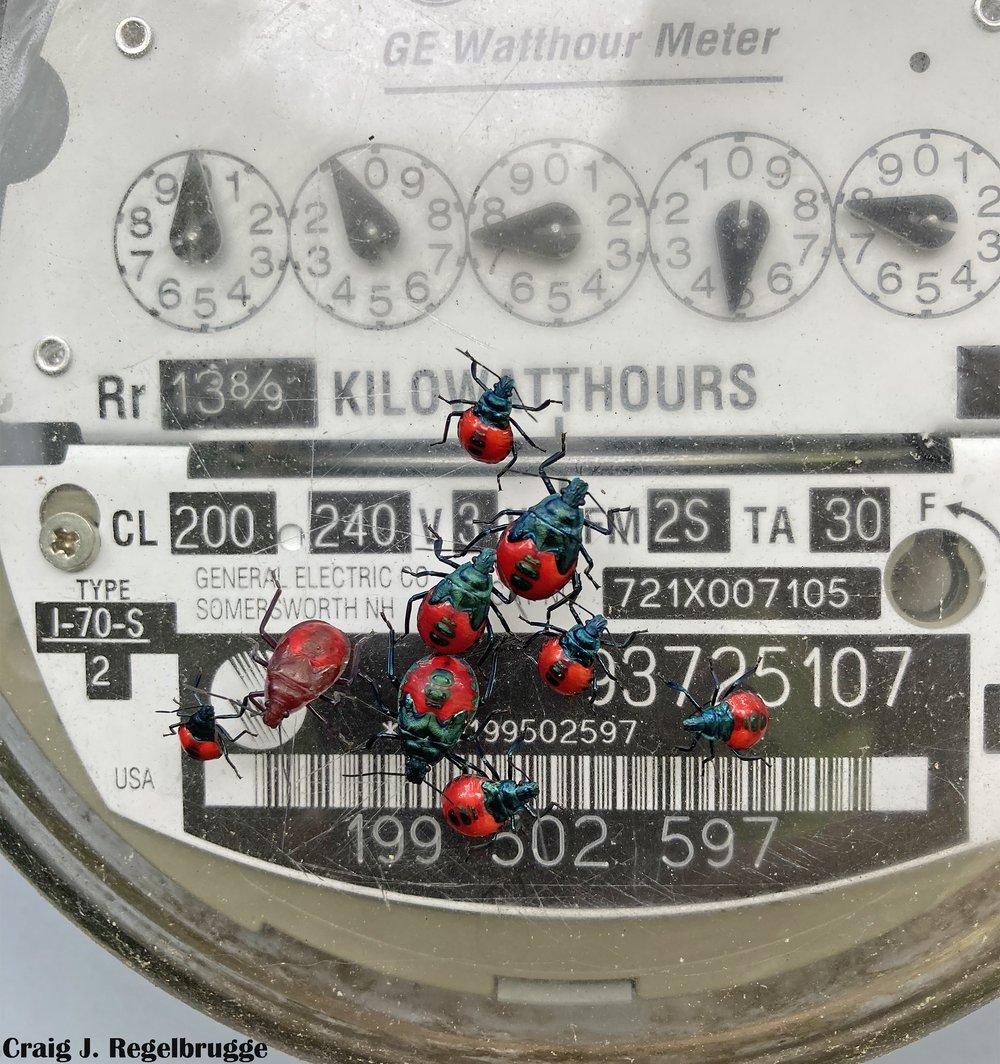

Signs of Pest Activity

Rodents aren’t the only destructive force that can invade your property. Other pests pose a risk to buildings, people, and pets. Bed bugs, for example, are a year-round issue faced by people across the world. Signs of these creepy crawlies include blood spots on sheets and itchy bites on people. Other pests to keep an eye out for include the following:

Bees, Hornets, and Wasps

These pests are feared for their sting but beloved for the critical role they play in sustaining agriculture and our environment. Bees, hornets, and wasps pollinate flowers and crops, ultimately helping to sustain life on our planet. Signs of an infestation include the presence of nests, which may be freestanding or located in dead wood crevices or below ground. Many people don’t realize they have an infestation until they notice increased insects buzzing around the area.

Mosquitos

Mosquitoes have a characteristic buzzing sound and create itchy bites. These pests thrive in damp areas, with females laying eggs on the surface of stagnant water. Mosquitoes can grow in water as shallow as 1/4 inch deep, or roughly the size of a bottle cap. Removing standing water can help prevent infestations.

Ticks

Ticks feed on the blood of humans and other mammals, along with birds and reptiles. These ectoparasites can carry diseases like Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. When they haven’t fed, ticks are typically small and difficult to spot. Once they feed, their oval-shaped, eight-legged bodies expand, increasing their visibility. Some of the most common spots to find ticks on the body include the thigh, waist, stomach, and groin. Ticks may climb to the upper body, but they tend to prefer warm, moist areas.

How to Prevent Potential Infestations

No matter what type of winter we experience, it’s essential to prevent infestations to keep your property and the people you care about safe and healthy. Catseye Pest Control has been helping prevent and mitigate pest infestations since 1987. Pest control success depends on multiple factors, and lasting results requires a partnership between you and professionals. For example, regularly wiping down counters and floors, storing food in rodent-proof containers, and securing garbage in tightly lidded receptacles can help aid in prevention.

However, even these steps don’t eliminate risk. Sealing openings, even small gaps and cracks in foundations, soffits, and other areas, helps stop pests before they start. Cat-Guard, our rodent and wildlife exclusion system, offers a safe, humane, chemical-free solution. This permanent barrier protects vulnerable areas to prevent pests from entering the property.

Likewise, programs like Platinum Home Protection provide year-round monitoring and preventive services. This allows experienced technicians to keep a watchful eye on your home or business and stop infestations before they grow into large-scale problems.

Contact Catseye to Learn More

Explore our services online or call us at 888-291-9238 if you need immediate help. Our experts are always happy to answer questions or provide additional information. Contact us today to get started with a free inspection.

The post Do Winter Temperatures Predict Pest Activity? appeared first on Catseye Pest Control.

This article appeared first on Catseye Pest