Don’t fear male cicada killer wasps, Sphecius speciosus

Male cicada killers are harmless and beautiful…well, unless you are another male cicada killer.

In previous episodes we visited sensational Asian giant hornets, a.k.a. murder hornets, and some of their look-alikes including European hornets and cicada killer wasps. Last week I received an inquiry about male cicada killers. A curious homeowner wondered if they were harmful to humans. This week we revisit an episode from a few years ago to learn about these amazing aerial acrobats. Sit back and relax, male cicada killers are harmless to humans but female cicada killers are lethal to annual cicadas. Female cicada killers kill cicadas as a food source for their young. During the daytime, female cicada killers hunt prey in the treetops where annual cicadas are found. Once captured and paralyzed, cicadas are interred in subterranean crypts. To see how female cicada killers roll, please check out this episode of Bug of the Week, “Cicadas beware, the ladies are in town: Female cicada killer, Sphecius speciosus”.

Although they appear fierce and perhaps even dangerous, male cicada killers pose no threat to humans or pets. Only females have a stinger, and try as he might, the male’s jaws and genitalia failed to puncture my skin. However, I have heard tales of females delivering a memorable defensive sting when inadvertently stepped on or trapped under knee or hand. Video credit: Paula Shrewsbury, UMD

But in advance of the appearance of the ladies, two male cicada killers established territories about twenty feet apart in my flower bed. So began a fierce competition for dominance of space and, I suppose, eventual access to the babes soon to emerge from the earth. Each morning shortly after sunrise as the morning sun warms the land, two feisty males arrive at their respective perches, one on a short yew bush and the other on the nozzle of my garden hose. As you will see in the video, they are on high alert, frequently leaving their perch for a short flight. Not quite understanding the thinking of the wasp mind, I imagine these forays are designed to provoke a battle with the other hopeful suitor. Occasionally, these sorties extend far enough from the perch that one male will enter the territory of the other. This results in a remarkable battle complete with frenetic buzzing and males interlocked in flight. It appears much biting and kicking goes on as evidenced by the response of a cicada killer when I captured one and held it. Eventually one breaks away and skedaddles toward my neighbor’s lawn with the victor in hot pursuit. But the victory seems fleeting. Male cicada killers either have remarkably short memories or indefatigable egos as the aftermath of these vicious mêlées soon results in both males returning to their perches only to repeat the battle a short time later.

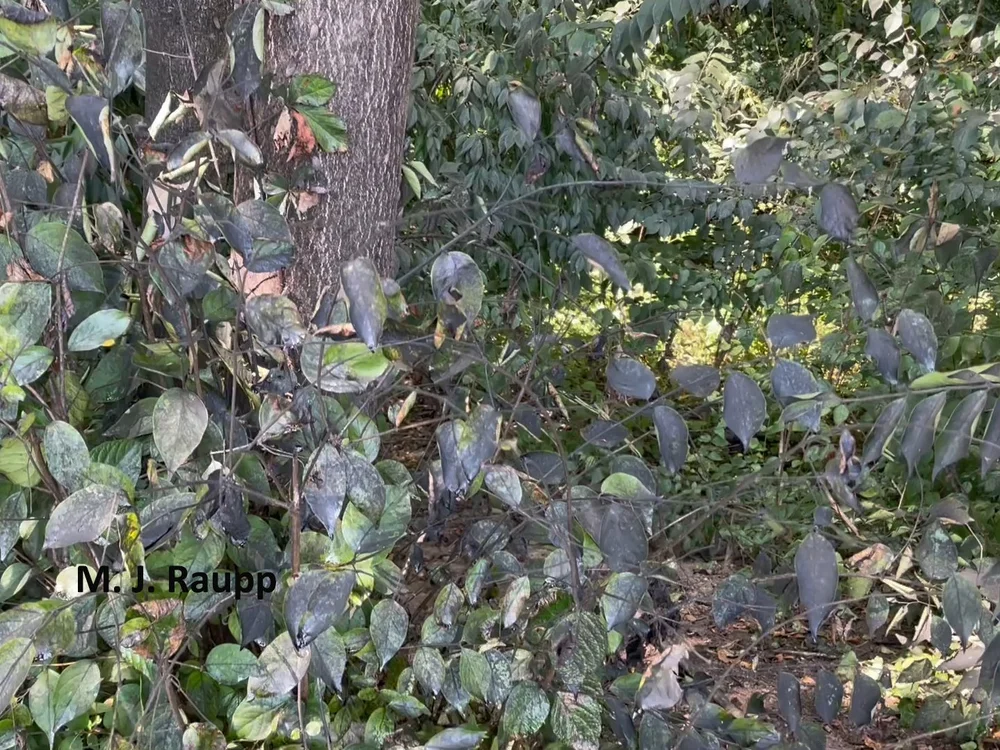

One perched on a shrub, the other perched on my garden hose. These two fellows are pumped and looking for a tussle. Short forays from the perch sometimes result in spectacular aerial battles as each tries to lay claim to the territory where females will soon appear. Video credit: M. J. Raupp

Perhaps one sunny morning only one of these fierce flyers will remain and the vanquished will have departed for less ardently defended turf in search of his own mate. But for now, with coffee in hand, this is the best early morning bug show in my garden.

Acknowledgements

For more information about cicada killers including videos of them in action, please visit Chuck Holliday’s magnificent cicada killer website, BIOLOGY OF CICADA KILLER WASPS.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week