At night in the rainforest with scary whip spiders: Amblypygids

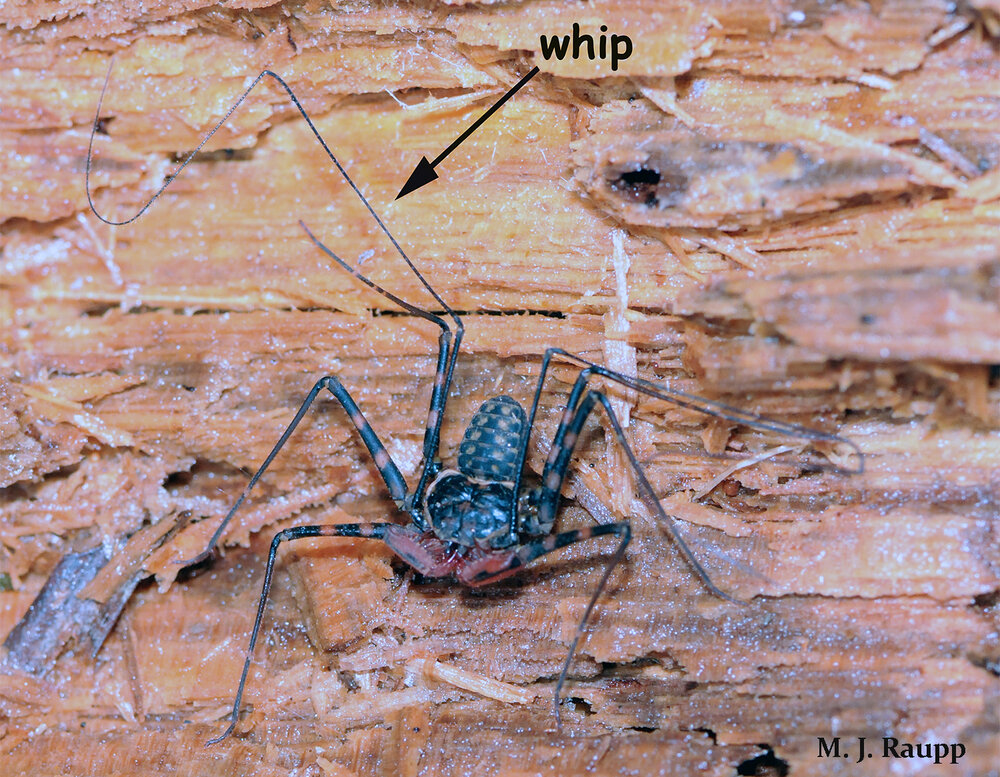

Greatly elongated front legs enable the whip spider to sense food, mates, and danger.

As Old Man winter refuses to completely relinquish his grip on much of North America, Bug of the Week continues its adventures in warmer places. In recent weeks we visited charming chinchemolles in Chile and beautiful fungus beetles in the Amazon Basin. This week we cross the equator and head 1,750 miles north to the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica for a nighttime encounter with one of the creepiest arachnids on the plant, the whip spider, aka tail-less whip scorpion or amblypygid. To witness the grim mien of this creature, one must don a headlamp, grab a flashlight, and plunge into the rainforest, best done with a trusty guide. Unlike distant relatives that often hunt by day, like crab spiders and jumping spiders, these denizens of the dark lurk in caves, hide in hollows beneath rocks, galleries in the soil, or holes in trees during daylight hours. By night they hunt and ambush prey.

Once these spines get you, there is no escape.

While other arachnids such as spiders and true scorpions amble about on four pairs of legs, whip spiders use just three pairs for their nocturnal strolls. The fourth pair of legs found at the front of the creature is extraordinarily long and loaded with sensory structures to detect odors and objects including mates, offspring, and prey. These so called “whips” can be three to six times the length of the body and give the whip spider its common name. Whips can move in almost a complete circle around the amblypygid and are very useful for detecting objects ahead, behind, above, and to the sides of the creature in a world of darkness. Just in front of the whip-like legs is a pair of scary hinged appendages known as pedipalps. Pedipalps snag prey in much the same way the powerful forelegs of the praying mantis capture their victim. As a tasty morsel enters range, a rapid strike of the pedipalps ensnares the prey in comb-like teeth. Usual meals include crickets, cockroaches, spiders and moths, but small lizards and even fish are known to be eaten by these fierce predators. Once captured, the victim is pulverized by two grinding jaws called chelicerae. Digestive enzymes are added to the pulpy mass and the whip spider ingests the liquefied meal.

A nighttime walk along a rainforest trail is full of spooky encounters, including ones with amblypygids. Watch as the whip spider senses the approaching danger of a giant finger and jets out of harm’s way. At one tenth of normal speed see how the whip-leg of the arachnid reaches back to examine the intruder before turning on the warp drive to escape.

As frightening as whip spiders appear, they are truly harmless to humans. In fact, some species have several admirable and somewhat endearing behaviors. One such behavior is a fine sense of direction. While wandering about the rainforest at night it is easy to get lost. On more than one occasion hapless adventurers have disappeared into a ravine while searching for a trail in dense tropical vegetation. Research has shown that some whip spiders can find their way home after being moved more than 30 feet away from their refuge, all this without Google maps. For any mothers who might be reading this episode, think about the calories you burn lugging youngsters about when they want to be picked-up. Whip spiders lay from 10 to 90 eggs at a time. Mother whip spiders typically carry their young on their backs for several weeks after offspring hatch from eggs. In captivity, females of the Floridian whip spider, Phrynus marginemaculatus, continue to interact with their offspring for several months after the babes have departed from their mother’s back. Mothers were observed to move between small clusters of young ones. In captivity, females and offspring frequently engaged in gentle mutual stroking with their whip-like legs. How often these fascinating behaviors happen in the wild remains to be seen. The message conveyed by the mutual stroking is known only to the whip spider and her young, but on a dark night in the Costa Rican rainforest, a gentle touch from mom could be a comforting signal even to a whip spider.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week gives special thanks to Carlos and the other nocturnal adventurers at Aguila de Osa who were the inspiration for this episode. Kenneth J. Chapin and Eileen A. Hebets’ treatise “The behavioral ecology of amblypygids”, and the wonderful article “Social behavior in Amblypygids, and a reassessment of arachnid social patterns” by Linda Rayor and Lisa Anne Taylor, were used as references for this episode. To learn more about whip spiders, please visit the following website: https://theethogram.com/2018/01/23/creature-feature-tailless-whip-scorpion/

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week