Plants as camouflage – who thought of it first? Meet the camouflaged looper, Synchlora aerate

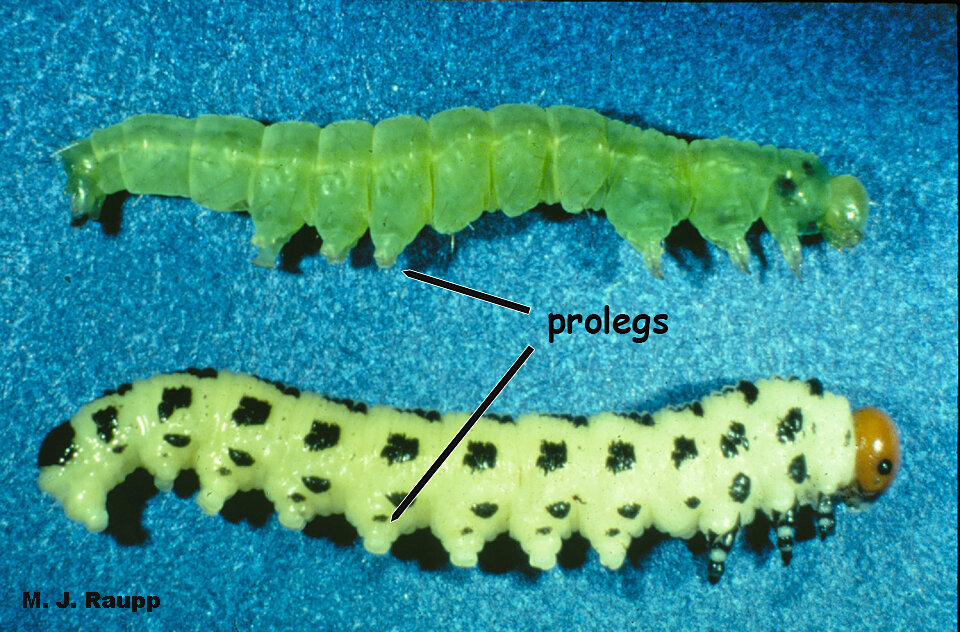

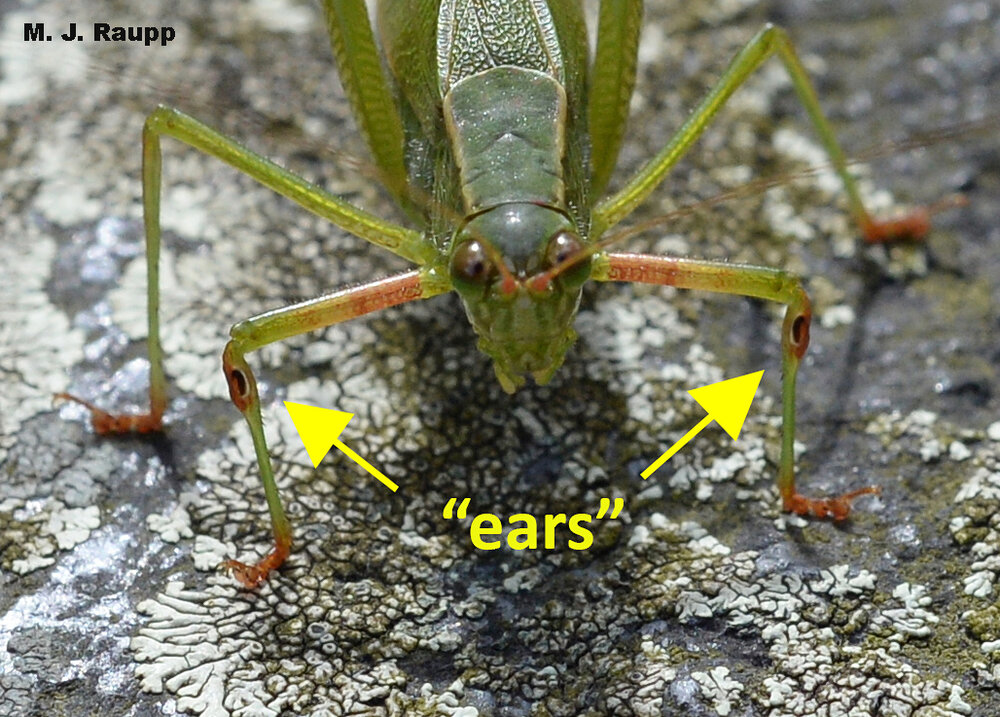

Ok, if you can find the caterpillar, on which end is the head, left or right?

A blossom full of frass is a pretty good clue that a caterpillar may be lurking nearby.

Several years ago while at work pulling weeds in a bed of chrysanthemums, I noticed a liberal sprinkling of caterpillar frass decorating blossoms of several plants. Frass, the euphemistic term for the pellet-like, powdery, or sawdust-like excrement of herbivorous insects, often provides a clue alerting one to the presence of an insect on or in a plant. A thorough inspection of my mums failed to disclose the culprit, but as I watched the plant later while enjoying a leisurely cup of coffee, I noticed a small cluster of flowery debris swaying on a blossom. A closer inspection revealed a cleverly disguised caterpillar cloaked in purple petals busily dining on the flower head. Recently, several eagle-eyed naturalists have reported similar sightings on mints and Joe Pye weeds in gardens and meadows. While I have yet to discover them in my garden this season, if the rain ever abates, I will renew my search with vigor.

This little trickster is the camouflaged looper, Synchlora aerate. Bedecked with bits of foliage and flower petals, it is sometimes detected when performing a herky-jerky waltz as it moves from one meal to the next. We’ve all seen the movie where a warrior incorporates leaves and branches into a camouflaged uniform to hide from the enemy, right? Next time you see this in a flick, just remember that a caterpillar thought of it first several million years ago. If you have a moment to sit and watch a stellar performance you may see the looper sway back and forth, adding to the illusion of a plant part being blown by the wind.

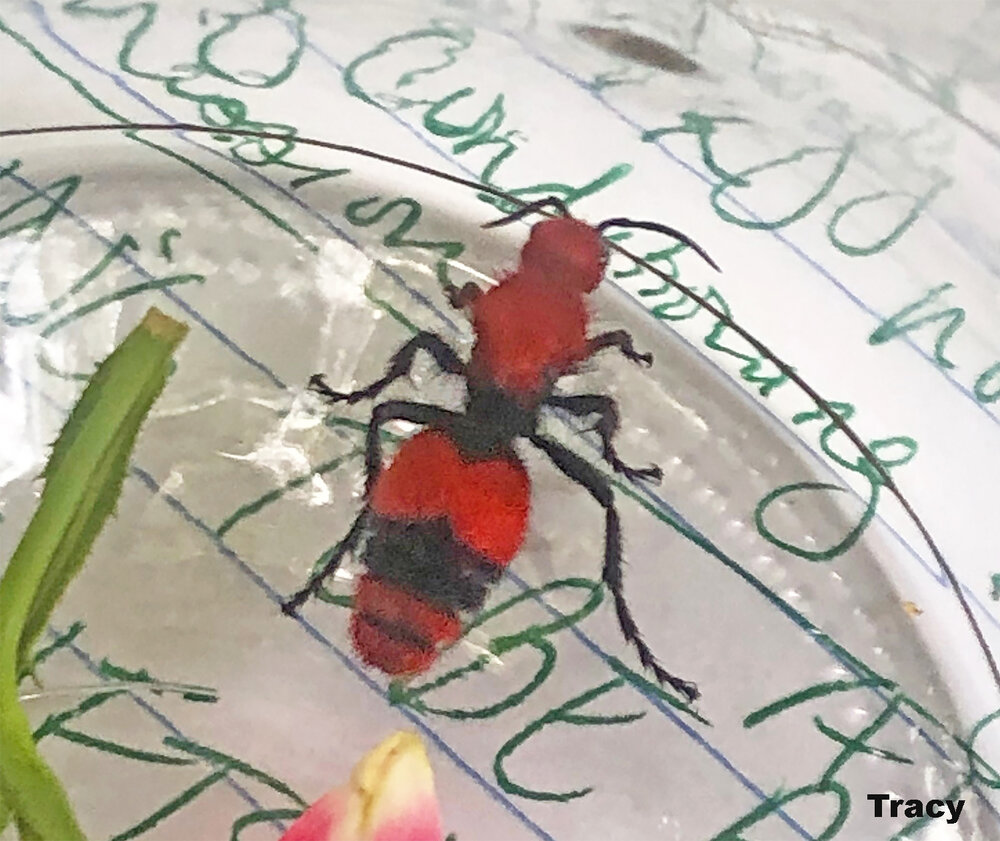

Imagine you are a camouflaged looper. When dining on coreopsis, browns and yellows seem the smart camo choice. But when crimson mums are on the menu, better go with the crimson petals. And when you depart for the next meal add a little “I’m just a petal swaying in the breeze” movement to your routine to fool the eyes of hungry predators.

The camouflaged looper turns into the pretty wavy-lined emerald moth.

Loopers are members of a large family of moths known as geometrids. The name geometrid stems from Greek roots meaning “earth measure”. Another common name for some geometrid caterpillars is inchworms. As they cruise about the blossoms, loopers and inchworms do appear to measure the earth inch by inch. In addition to my chrysanthemums, camouflaged loopers eat many other types of flowers including ageratum, aster, black-eyed Susan, boneset, coreopsis, daisy, goldenrod, Joe Pye weed, ragweed, raspberry, rose, sage, St. John’s wort, and yarrow. The adult stage of the camouflaged looper is known as the wavy-lined emerald and it is every bit as beautiful as the larva. So next time you see some unexpected frass on your flower blossoms, take a few moments to observe your flowers with an eye out for these masters of disguise.

Can you spot the camouflaged looper on this mint? Well, for the one eating goldenrod some labels and an arrow might help. Photo credits: mint – Mara McCall, goldenrod – Mike Raupp.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to our observant naturalists who discovered camouflaged loopers in their landscape, especially Mara McCall and Glen Schulze for providing the inspiration for this episode and for providing cool images of these rascals. The wonderful reference “Caterpillars of Eastern North America” by David Wagner was used as a reference for this Bug of the Week.

BTW, in the feature image the head is on the left and the rear end is on the right.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week