What are those strange green wrapped leaves in unusual places? Leafcutter bees, Megachilidae

Strange tubes of rolled leaves within a vent of a lawn mower are the handiwork of a leafcutter bee. Image credit: Darlene Wells

This week we dip into the Bug of the Week mailbag to answer a question regarding strange green bundles found inside a hollow vent of a garden tractor. Each bundle looked like a miniature cigar composed of dozens of small circular leaf sections carefully assembled into a cylinder. Each small wrapper contained tiny balls of pollen. These curious creations were the work of one of our most important and interesting native pollinators, the leafcutter bee. We met other members of the megachilid clan, mason bees and giant resin bees, in previous episodes.

Keep an eye out for circular cuts on leaf margins of trees and shrubs in your garden. These leaf clippings are used by marvelous leafcutter bees to build their nurseries.

Leafcutter bees leave other clues of their presence as they visit our landscapes. While gardening or simply communing with vegetation, you may have seen roses or other trees and shrubs with almost perfectly round circles of tissue removed from their leaves. The artisans behind these creations are leafcutter bees. These small hairy bees are solitary and do not build large colonies nor have queens and workers like honeybees or bumblebees. Each female leafcutter bee builds a nursery for her young. During summer, leafcutters construct nests in voids of trees, hollow branches, pithy stems of plants such as raspberries and, apparently, tractor vents. Once a suitable nest site has been found, the bee clips small circular sections of leaves and transports them back to the nest site where they are used to line a chamber within a void.

In the natural world, tubes constructed by leafcutter bees are often found in voids of trees.

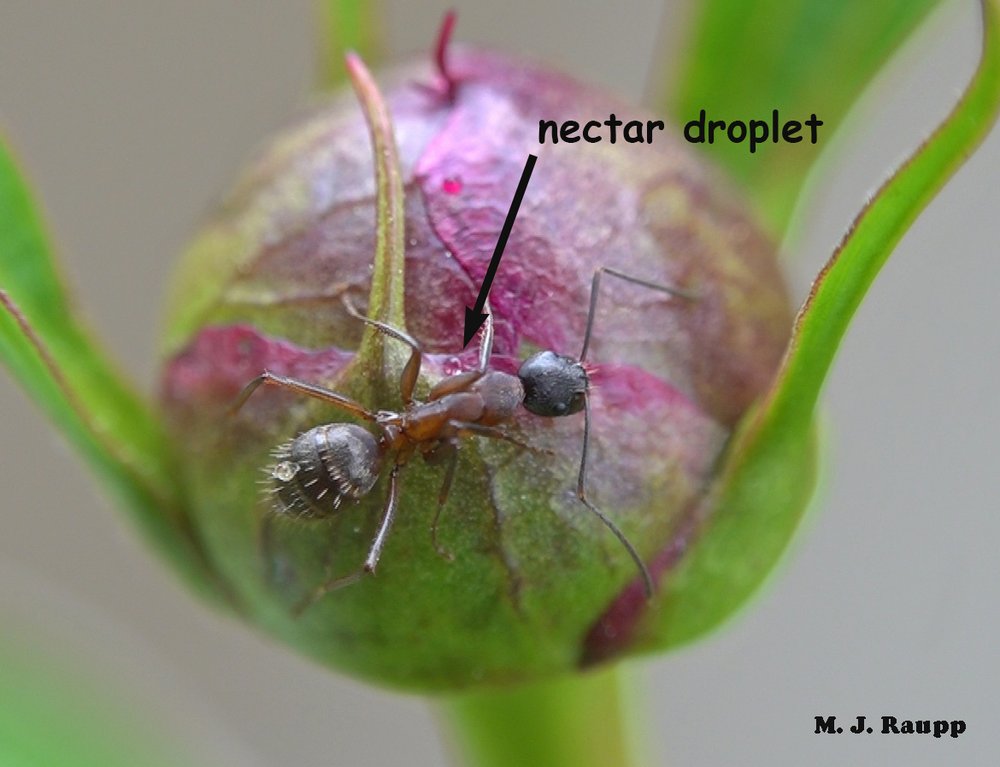

After assembling the leaf disks to form a hollow tube, the leafcutter gathers pollen and nectar from nearby flowers and packs the tube with nutritious floral provisions to form a cake. An egg is then deposited on the pollen cake and the next chamber in the nursery is built with leaf disks and stocked with pollen. This continues until several long tubes line the gallery. Eggs placed within the rolled leaves hatch into small legless larvae that eat the pollen. After the larvae have completed development, they form pupae from which emerge adult leaf cutter bees that spend the winter within the rolled leaves. With the arrival of spring and new supplies of tender leaves, nectar, and pollen, adult bees emerge and begin the work of finding mates and making brood chambers for the next generation of leafcutters.

Megachilids are regular visitors to my butterfly weed in the flower bed, to thistles in the meadow, and to a variety of other flowering trees and shrubs they pollinate. I slowed this female down by 60% so you could glimpse the pollen load from my cone flower carried on hairs called scopa on the underside of her abdomen. Look at that golden pollen, food for her babies.

Coming in for a landing and with its tongue hanging out, this European wool carder bee prepares to sip some nectar.

One interesting member of the leafcutter clan found here in the US is the non-native European wool carder bee. Wool carders build their nursery with fibers collected from plants or animals. Another sneaky part of the clan are parasites that do not build nurseries of their own. Instead, they deposit eggs in nests of other species of bees. After hatching, these intruders eat the young of their unfortunate host and usurp provisions meant for the offspring. These devious rascals are known as kleptoparasites.

Leafcutter bees are extraordinarily docile and unlikely to sting. As important pollinators of several agricultural crops including blueberries and alfalfa, and many native trees and shrubs, they deserve our care and attention to help preserve their vital ecosystem services. Keep an eye open for small hairy bees collecting pollen in your garden and try to observe their precise handiwork on your curiously clipped leaves.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Darlene Wells for sharing her images of leafcutter tubes and providing inspiration for this episode. We also thank bee guru Sam Droege for help identifying our leafcutter bees.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week