Surprise visit by a queen: German yellowjacket, Vespula germanica

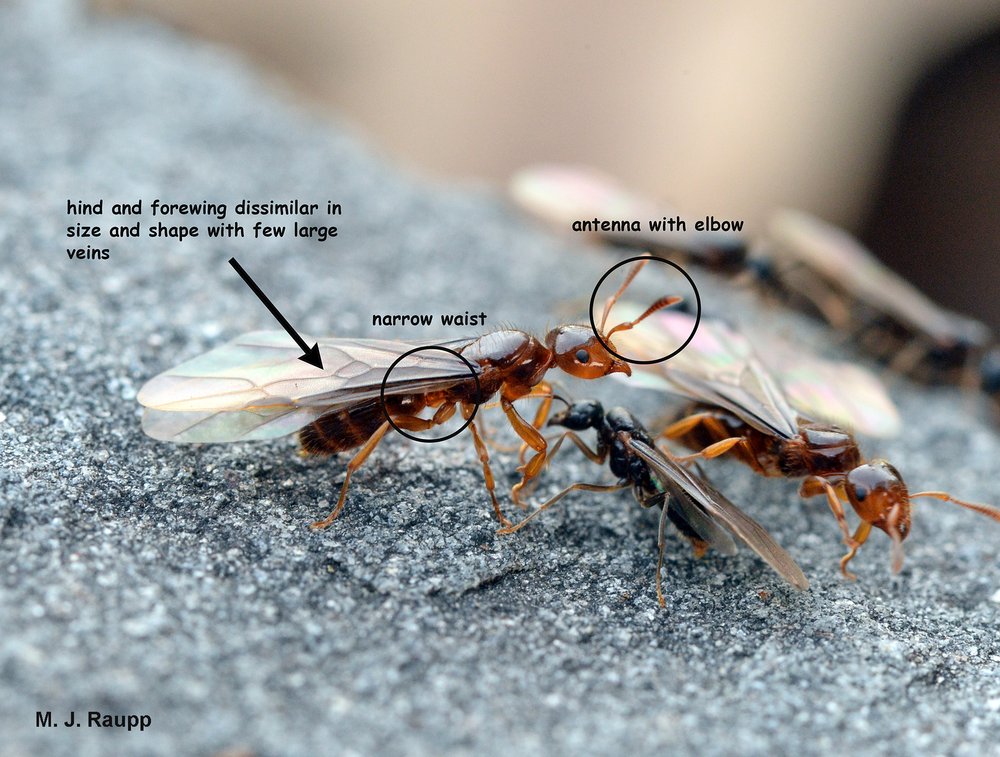

This docile German yellowjacket queen made an early appearance inside a home.

Last weekend while dining with family in their rural New Jersey home, we were thoroughly entertained by the aerial antics of a rather large wasp. This yellow and black beauty made several sorties from an undisclosed location in the kitchen and swooped about the chandelier suspended above the table. While zooming wasps might be disconcerting at some dinner parties, for bug geeks and their kin, a visit from hymenopteran royalty in the dead of winter is a welcome reminder that spring is not all too far away. To discover exactly who this fancy flier was and what she was doing at our winter repast, we turned to esteemed colleagues Drs. Nancy Breisch and Al Green, world authorities on six-legged creatures found indoors. Here is what the experts had to say. “You have captured the image of a beautiful queen of the German yellowjacket, Vespula germanica, and you are correct, she has mistakenly become active months before she should have. The first invaders to the U.S. (1970s) spread extremely rapidly because the overwintering queens, foundresses of the annual spring colonies, searched for voids in vertical facades (mostly building cavities), unlike the typical behavior everywhere else in the world where they concentrate on finding hollows in the ground to begin their nests. This meant they weren’t competing as much with our native Vespula species. All Vespula are cavity nesters and can nest almost anywhere but our natives are usually in the ground and for the first 10 to 15 years after invasion, V. germanica was usually in a structural void. When Vespula strikes it rich with a nice pre-existing void location, all the effort of enlarging the cavity (almost every worker leaving a ground nest has a mouthful of dirt) is channeled instead into making carton so their nests have much larger and thicker envelopes. By the 1980s, U.S. German yellowjacket populations began to display a higher incidence of the more characteristic ground nesting behavior. We found our first ground nest of V. germanica in a grassy area behind the long-lost Maryland Book Exchange (College Park, MD) in the late 1980s. Every year we collected for Johns Hopkins allergy research we could count on a nest in the dairy barn wall, and after that structure was torn down we got them year after year from a nest in the hay loft of the sheep barn.” A German yellowjacket queen, now that’s cool.

What could be better than dinner and a show? This pretty German yellowjacket queen emerged prematurely from her winter rest, fooled by the warmth of a home. After entertaining diners with aerial acrobatics and spending the night in a fruit bowl, she was relocated in a tool shed outdoors to chill-out and await the return of warm weather.

While making breakfast the following morning, we discovered the redoubt of our royal yellowjacket, who was hiding beneath an apple at the bottom of the fruit bowl. With her hibernal rest unwittingly ended too soon, she was not interested in any sort of aggressive behavior and we were able to admire her up-close and personal. After glamming for a few minutes, the queen grew a bit restless and after taking a poll, we decided to relocate the royal. The new residence for the queen would be a nearby tool shed. Hopefully, she will settle in this unheated structure and await the arrival of true spring when she can initiate her colony and produce workers. Workers will help rid our plants of soft-bodied insect pests and assist in the awesome task of pollination. Wasps and wasp nests also provide a nutritious source of food for mammals including bears, raccoons, and skunks, and several species of birds. Yellowjackets will, of course, heroically defend their nest, which sometimes require extirpation if humans or pets are imperiled.

You can learn more about yellowjackets at these episodes of Bug of the Week: Beware of zesty drinks: Yellowjackets, Vespula, bumble bees, Bombus, and honey bees, Apis, can really spice up soft drinks; and Be careful around yellowjackets: Eastern yellowjackets, Vespula maculifrons.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Gordon and Sheri for providing the backdrop for this week’s episode in their dining room, and colleagues Drs. Nancy Breisch and Al Green for the remarkable account of V. germanica.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week