I see icy isopods: Pillbugs, terrestrial Isopoda

Pillbugs are crustaceans and more closely related to crabs than to insects. They play an important role as recyclers of organic matter. Image credit: Paula Shrewsbury, PhD

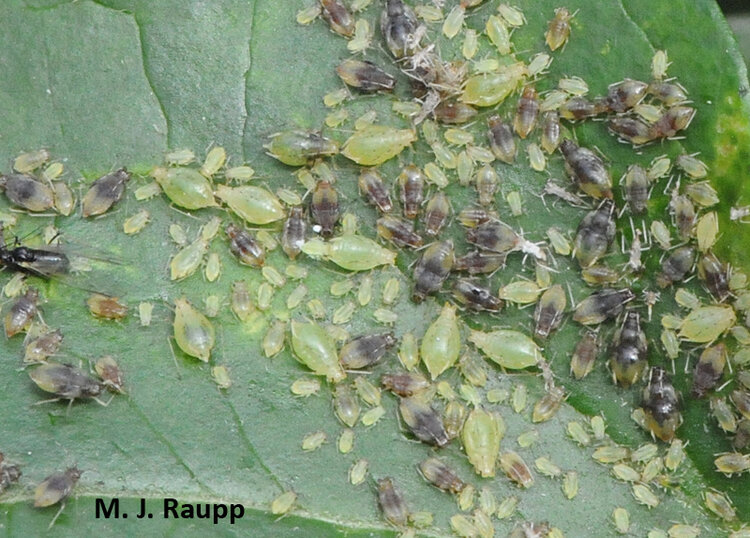

On chilly days, most small invertebrate creatures like insects are locked in winter torpor awaiting spring’s warmth. However last week, following a nighttime low in the teens and with hoar frost still on the ground, I was delighted to see a gang of pillbugs, a.k.a. rollie pollies, sowbugs, potato bugs, or woodlice, slowly going about their task of recycling organic matter beneath a large bolt of a fallen ash tree. Unlike predators such as lady beetles or praying mantises that occupy exalted places high in the food webs, detritivores occupy lower rungs on the ladder of life. Detritivores are key players in Mother Nature’s clean-up crew. Their important task is to eat dead and decaying things such as fallen plants and return minerals locked-up in leaves, fruits, and woody tissues to the nutrient cycle. We visited other recyclers in previous episodes including rhinoceros beetles, millipedes, termites, and bess beetles.

Early one morning, with frost still on the ground, a scrum of pillbugs huddles beneath a log. As the early morning sun warms their bodies, fourteen legs help them skitter from the sunlight to find danker refuge beneath the bark.

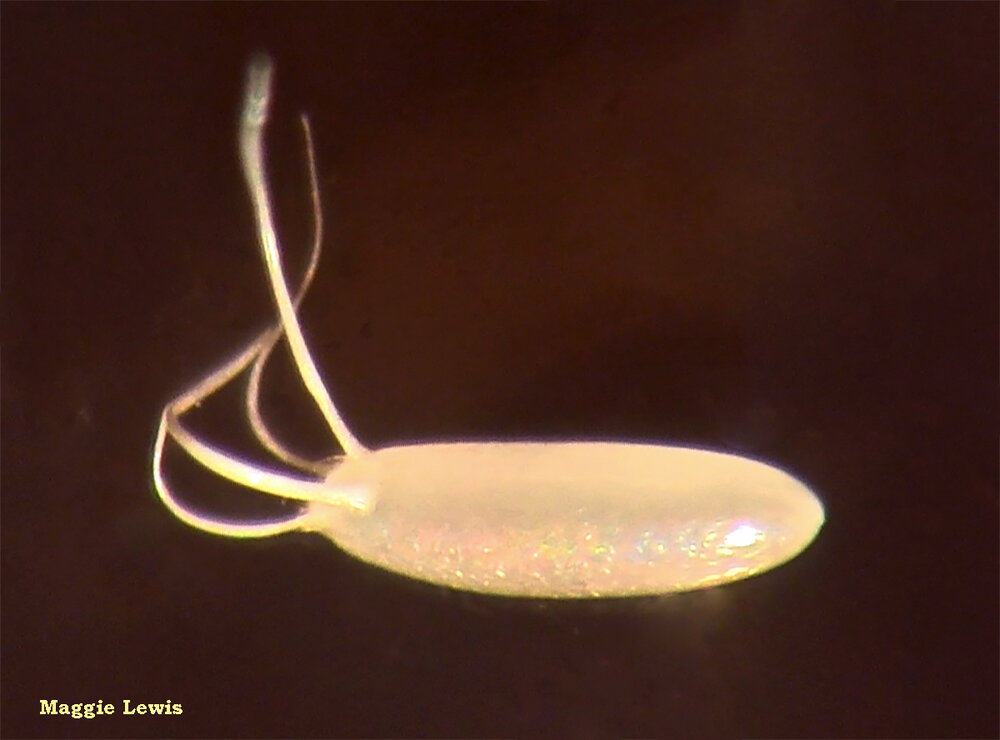

The ability to roll into a tight ball resembling a pill gives pillbugs their name.

Isopods are not truly bugs, so please excuse their guest appearance in Bug of the Week, but they are odd and fascinating members of the arthropod clan. They belong to a group of hard-shelled creatures called the crustaceans. Crustaceans include tasty, familiar edibles like crabs, lobsters, and crayfish. Isopods commonly occur in marine environments where they eat algae, diatoms, and decaying vegetation. Eons ago, some adventurous members of the isopod lineage moved from the sea to the land. These explorers were the ancestors of the isopods commonly found beneath logs in the forest and those in my compost heap. Most gardeners know these curious creatures by the names pillbug or sowbug (a closely related terrestrial crustacean). The name pillbug stems from the ability of many species of these isopods to roll into a pill-shaped ball when threatened much like an armadillo. This defensive posture makes the tender underbelly of the pillbug difficult to reach. Armor-like plates on its back shield the pillbug from attack.

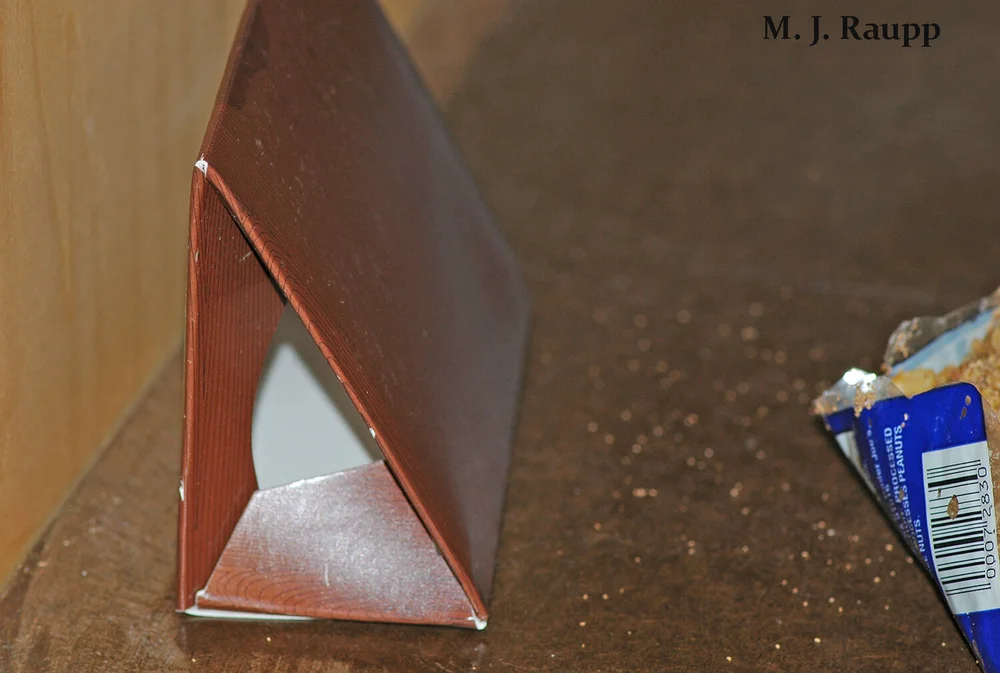

With the return of warm weather, pillbugs will once again begin the important job of recycling my leftover vegetables. And in this taste test, it looks like carrots are preferred to tomatoes.

Pillbugs are common in moist habitats beneath leaf litter, compost, rotten logs, boards, and stones. Moisture is a key element in the life of isopods. Even though they have escaped the confines of a life aquatic with their colonization of land, these true crustaceans still rely on gills for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide and those gills must remain wet. Unusually wet seasons like ones we have experienced in recent years create favorable conditions for explosions of pillbug populations. While pillbugs and sowbugs play an important role as recyclers, when too numerous they may damage the tender roots and stems of plants in greenhouses or gardens. Folks sometimes are dismayed when pillbugs appear in basements or garages as they move about in search of dead things. You can thwart entry of pillbugs into your home by using a few simple tricks: keep mulch away from foundations, maintain door sweeps, and caulk openings to discourage unwanted visitors from entering your home. With the return of warm weather in a few months, my compost heap will be a smorgasbord of rotting vegetables and, without fail, pillbugs will appear from the moldering depths of the bin eager to recycle plant remains.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Shrewsbury for wrangling lumber, photographing pill bugs, and providing inspiration for this Bug of the Week.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week