Beleaguered boxwoods beware, box tree moth, Cydalima perspectalis, arrives in the DMV

There is no mistaking this caterpillar on a boxwood. This is the larva of the box tree moth. Paula Shrewsbury image

From the time of our earliest European colonists, boxwoods have been important components of ornamental landscapes. Boxwoods grace iconic landscapes in the DMV including George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon, the “Box Walk” at Dumbarton Oaks, the National Boxwood Collection at the United States National Arboretum, as well as hundreds of public and private gardens and landscapes in our region. However, boxwoods are one of the most problem-prone plants in our landscapes. Already beset by exotic pests including leafminers, spider mites, and pathogens such as boxwood blight, boxwoods in the DMV and throughout our country now face a new, lethal non-native invader, the box tree moth. Like many of our new invaders box tree moth is native to Asia in China, Japan, and Korea. Probably due to the movement of ornamental plants, it entered Europe and was first discovered in Germany in 2007. It now occupies more than 30 Eurasian countries. It jumped across the Atlantic to Canada where it was detected in 2018 and arrived in the United States with shipments of nursery plants from Canada in 2020 and 2021. Prior to July, 2025 it spread to Delaware, Massachusetts, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and New York. Yes, the DMV was surrounded and sure enough, it was detected in Clarke and Loudoun Counties in Virginia and three locations in Washington County in Maryland during the latter half of July and early August.

Iconic boxwoods are one of the most widely planted shrubs throughout the country and here in the DMV. Beset by pests like leafminers, spider mites, and boxwood blight, they now have a devastating new enemy, the box tree moth. Caterpillars of box tree moth defoliated these once handsome boxwoods. The shrubs will be destroyed in hopes of slowing the spread of the moth. Watch as hordes of caterpillars consume foliage until only midveins and silken webs laced with nasty frass remain. In addition to destroying the boxwoods, these miserable leaf-munchers will sometimes eat each other. If your boxwood looks like this, and you see these, please contact your state department of agriculture or university extension service.

What’s the worry? If undetected, an infested boxwood can support a rapidly expanding population of leaf-eating caterpillars capable of completely defoliating large boxwoods. In addition, they create large silken webs littered with frass that accumulates on plants and on surfaces below.

How is this possible? Adult boxwood tree moths lay multiple clutches of 5 to 20 eggs. Larvae that hatch from the eggs are voracious herbivores that first remove green leaf tissue as youngsters and later consume entire leaves. And if this was not bad enough, after leaves are consumed, they feed on woody tissues thereby girdling stems and branches, hastening boxwood death. One generation of this carnage is bad enough, but box tree moth will have many generations in the DMV. In other locations, as many as 4 or 5 generations may occur annually depending on temperature regimes.

This pretty box tree moth is the new invasive culprit behind the threat to our boxwoods. Joe Boggs, OSU.

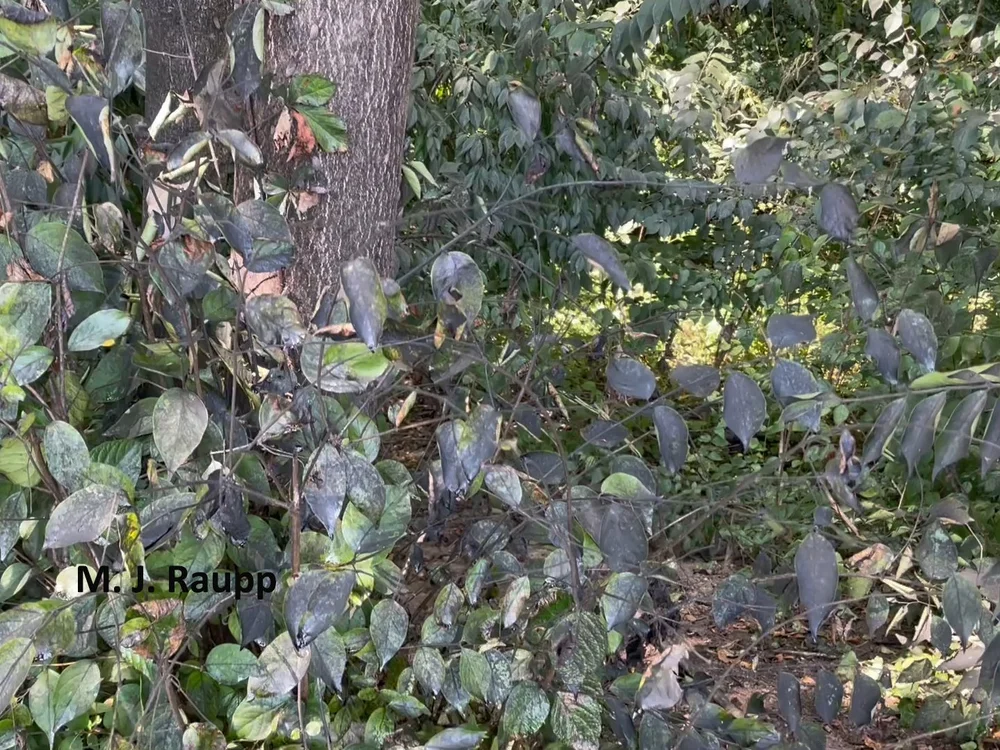

What should you look for? Discoloration, a change in the color of leaves from vibrant green to dull brown or gray and defoliation, the loss of parts or entire leaves are often the first and most easily recognizable clues that your boxwoods may be infested with box tree moth. Since no native moth or butterfly has caterpillars that readily eat leaves of boxwoods, the presence of large numbers of strikingly colored black, green, and yellow striped caterpillars with black heads is a dead giveaway for the presence of box tree moths. However, several other arthropod pests and diseases can cause discoloration, defoliation, and dieback on boxwoods. Fortunately, Joe Boggs of The Ohio State University has complied a wonderful pictorial guide to diagnosing boxwood pests and diseases including symptoms and signs of box tree moth.

Defoliated leaves covered with silk and hordes of caterpillars decked out in stripes and spots of green, yellow, white, and black with shiny jet-black heads mark an infestation of box tree moth caterpillars. Paula Shrewsbury image

Discolored leaves of these boxwoods could be due to several biotic or abiotic factors. A closer investigation would reveal the telltale presence of caterpillars. Paula Shrewsbury image

What should you do if you find box tree moth? The Maryland Department of Agriculture is presently engaged in a program to limit the spread of box tree moth. If you suspect you have this pest, the Department of Agriculture recommends the following:

· If you suspect your boxwoods may be infested with the box tree moth, please contact via email the Plant Protection and Weed Management program at [email protected]. Please attach a picture in your email.

· Allow Maryland or Federal agricultural officials to inspect your boxwood plants and place detection traps.

· Any infested material should be doubled bagged in plastic bags and placed in the trash.

· Nursery owners should monitor their boxwoods and implement safeguards to limit pest risk. All licensed nurseries should report BTM detections to the Maryland Dept of Agriculture Nursery Inspection Program or reach out to their nursery inspector.

Moving forward, what might the future hold for the box tree moth and us? Unfortunately, like emerald ash borers, brown marmorated stink bugs, spotted lanternflies and many other non-native pests of our landscape plants, the box tree moth is likely here to stay. However, Mother Nature in cooperation with humans often has a solution for these invaders. Indigenous natural enemies, predators, parasitoids, and pathogens often rally and put a beat-down on these non-native pests. Clever scientists search and discover natural enemies from afar and after exhaustive evaluation release them to reduce populations of invaders here in the US. Researchers develop chemicals to detect, attract, trap, and kill non-native pests. Even today several insecticides are available to kill caterpillars. Some of these contain active ingredients like Bacillus thuringiensis, a.k.a. BT, and spinosad which are dynamite for controlling caterpillars but safe enough to be used in organic food production. If you want to learn more about insecticides that can be used to manage box tree moth caterpillars, click on this link. With diligence, ingenuity, good science, and help from Mother Nature, we will find ways to manage this new noxious invader.

Box tree moth caterpillars can destroy an established stand of boxwoods like this one in a matter of weeks. Joe Boggs, OSU.

References and acknowledgements

“The fast invasion of Europe by the box tree moth: an additional example coupling multiple introduction events, bridgehead effects and admixture events” by Audrey Bras, Eric Lombaert, Marc Kenis, Hongmei Li, Alexis Bernard, Jérôme Rousselet, Alain Roques, and Marie‑Anne Auger‑Rozenberg was used as a reference for this episode. We thank Joe Boggs for generously allowing us to use his wonderful images of box tree moth. The inspiration for this episode came from Phyllis and Rod who allowed us to photograph their boxwoods and caterpillars. Please visit Box Tree Moth by Madeline Potter to learn more about this pest and explore links to additional information.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week