Bugs in orange and black: A spooky Halloween trick for predators, Small and large milkweed bugs, Lygaeus kalmii and Oncopeltus fasciatus

Small milkweed bugs are members of the cabal of milkweed feeders that sequester noxious cardiac glycosides from their host plant, a nasty trick on would-be predators.

In keeping with our Halloween tradition of meeting bugs dressed in orange and black, this week we visit two beautiful and perhaps deadly denizens of milkweed, small and large milkweed bugs. These harlequin rascals were super abundant on my butterfly weed, Asclepias tuberosa, throughout summer and fall. Many insects that consume milkweed, such as monarch butterfly and milkweed tussock moth caterpillars, milkweed leaf beetles, and milkweed longhorned beetles we met in previous episodes, display vivid patterns of orange or red and black. Some, like monarch and tussock moth caterpillars, obtain noxious plant chemicals called cardiac glycosides, heart poisons that are sequestered in their bodies after consuming milkweed leaves. These poisons are distasteful to a wide range of predators and thwart attempted acts of predation by visually gifted hunters, including birds and praying mantises. The phenomenon of developing an easily recognizable color pattern by two or more nasty-tasting insects that share one or more common predators, is called Müllerian mimicry, so named for the visionary German naturalist Fritz Müller.

However, the milkweed leaf beetle (not to be confused with today’s subject, the milkweed bug) does not store noxious chemicals from the milkweed. Its scam is to wear orange and black, thereby dissuading enlightened predators from an attack once they have learned that “orange and black” spells “nasty meal.” This type of mimicry, in which warning colors of a distasteful species like the monarch butterfly are copied by a tasty mimic like the milkweed leaf beetle, is called Batesian mimicry. The great English naturalist Henry Bates first described this form of mimicry while studying butterflies in Brazilian rainforests.

Whether dashing about on the ground or hiding within a curled seedpod, this mating pair of small milkweed bugs are inseparable despite some impatient foot tapping by the female.

Two other charter members of the Müllerian mimicry gang are small and large milkweed bugs, for they too store nocent cardiac glycosides after consuming the milkweed plants that serve as their source of food. This year was spectacular for milkweed bugs and my butterfly weeds generated hundreds. In spring and early summer, milkweeds thrived and produced early clusters of seeds mostly devoid of hungry milkweed bugs. Early in summer, only a few small milkweed bugs could be seen sneaking around the developing seed heads. However, by late summer and early autumn my milkweeds were colonized by teeming legions of beautiful large milkweed bugs. Where did the bugs come from and why did they suddenly appear well into the growing season?

Watch as recently hatched milkweed bug nymphs hiding in a seedpod develop into nymphs with ever-expanding wing buds, which finally transform into wings fit to power milkweed bugs to their southern wintering grounds.

Predators beware of an unpleasant dining experience if you ignore the spooky Halloween colors displayed by large milkweed bug nymphs.

Most people don’t realize that large milkweed bugs, like monarch butterflies, undergo annual migrations throughout much of the range of milkweeds, from southern states and Mexico where they spend the winter, to northern states and southern Canada where they spend the summer. Large milkweed bugs cannot survive winter’s chill in northern climes. Their annual migration south is triggered by shortening day length, cooling temperatures, and declining quality of milkweed plants as food. Titers of a glandular product called juvenile hormone signal the milkweed bug’s ovaries to take a “time-out”, and trigger flight behavior that transports the milkweed bug to warm southern lands where milkweeds grow. Once the southward migration is complete, juvenile hormone levels rise, ovaries are switched on, and reproduction resumes. In spring, the migratory pattern reverses and generations of large milkweed bugs leap-frog their way northward to colonize milkweeds as far north as Canada. Small milkweed bugs are more of the ‘we don’t like to travel much’ kind of an insect, and as such they eschew annual long distance migrations and stick around near home.

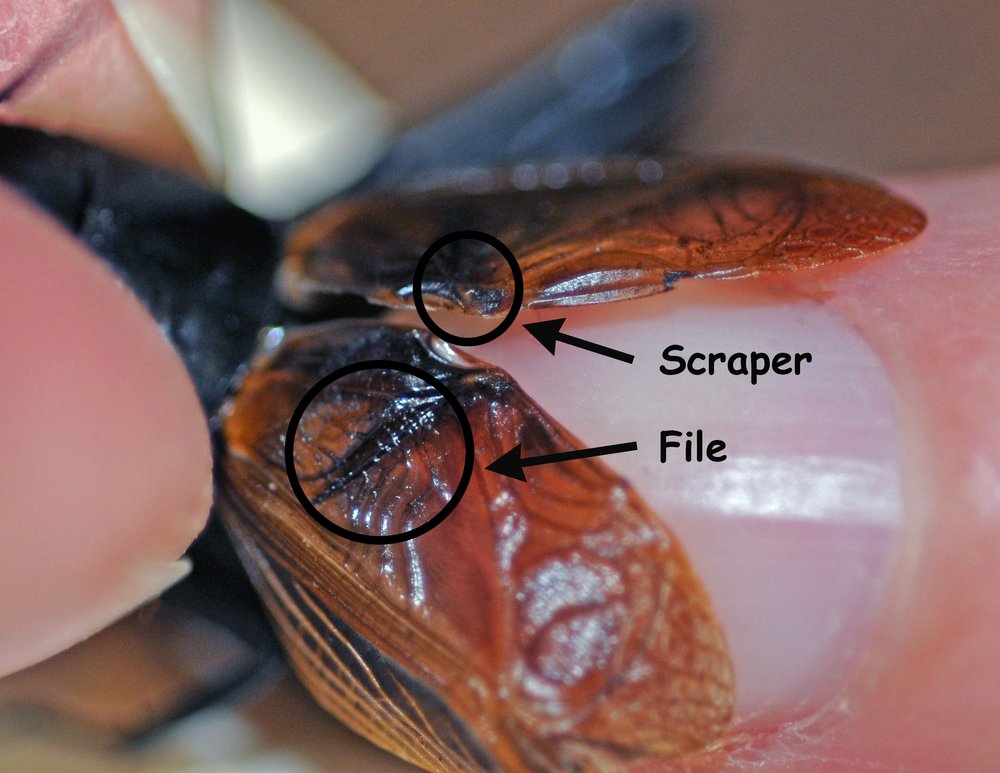

As members of the seed bug clan, milkweed bugs insert a long slender beak into the ripening seeds within the developing pod. After injecting digestive enzymes into the seed, they suck liquefied food through the straw-like beak into their gut where nutrients will be used for growth, development, and reproduction. During her lifetime, the female large milkweed bug may lay up to 2,000 eggs. Small reddish-orange and black nymphs hatch from the eggs and eat seeds of milkweed. As nymphs grow and develop, small black wing buds become clearly visible on the body segments just behind the head. These wing buds enlarge as the insect feeds and molts, until the final transformation to the adult stage when wings are fully formed and ready for flight. With a killing frost on the pumpkins just around the corner, the last few nymphs remaining on my milkweed better hurry and earn their wings to begin their trek south before winter’s chill brings an end to their milkweed revelry.

A large milkweed bug grooms its antenna with its forelegs. The business end of the milkweed bug is its tubular beak. At rest it is stored beneath the body. To access nutrients, the needle-like mouthparts probe through the husk of the seed head to reach nutrient rich seeds within.

Bug of the Week hopes you are getting ready for a spooky and fun-filled Halloween!

Acknowledgements

The wonderful reference “The Pleasures of Entomology” by Howard Ensign Evans was used as a resource for this episode. “Secret weapons” by Thomas Eisner, Maria Eisner, and Melody Siegler; “Mantids and milkweed bugs: efficacy of aposematic coloration against invertebrate predators” by May Berenbaum and E. Miliczky; and “The Small Milkweed Bug, Lygaeus kalmii (Hemiptera: Lygaeidae): Milkweed Specialist or Opportunist?” by Al Wheeler, Jr., provided valuable insights into the mysterious ways of this week’s stars.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week