From the Bug of the Week mailbag: World’s largest walking stick visits the Goddard Space Flight Center, Northern walkingstick, Diapheromera fermorata

A very large walkingstick appears to rest on the wall of a NASA building at the Goddard Space Flight Center near Washington, D.C. Image credit: Larry Coy

In October of 2008, The Natural History Museum of London headlined the discovery of the world’s longest insect, Phobaeticus chani, a giant stick insect from the rainforest of Borneo. This behemoth checked in at 22 inches in length and displaced the former record holder from Indonesia, Phobaeticus serratipes, another giant at 14 inches. Recently, Bug of the Week received a remarkable image of a walkingstick that make these gargantuans pale in comparison. The northern walkingstick in our feature image is at least 40 feet long. Yikes! Well, the clever photographer who took this crazy image assured me the camera magic that captured both the walking stick on a nearby window and the reflection of the NASA building behind him was not a trick of post-production. Whew, what a relief, but humans were never really in danger of being attacked by giant walkingsticks. They are vegetarians.

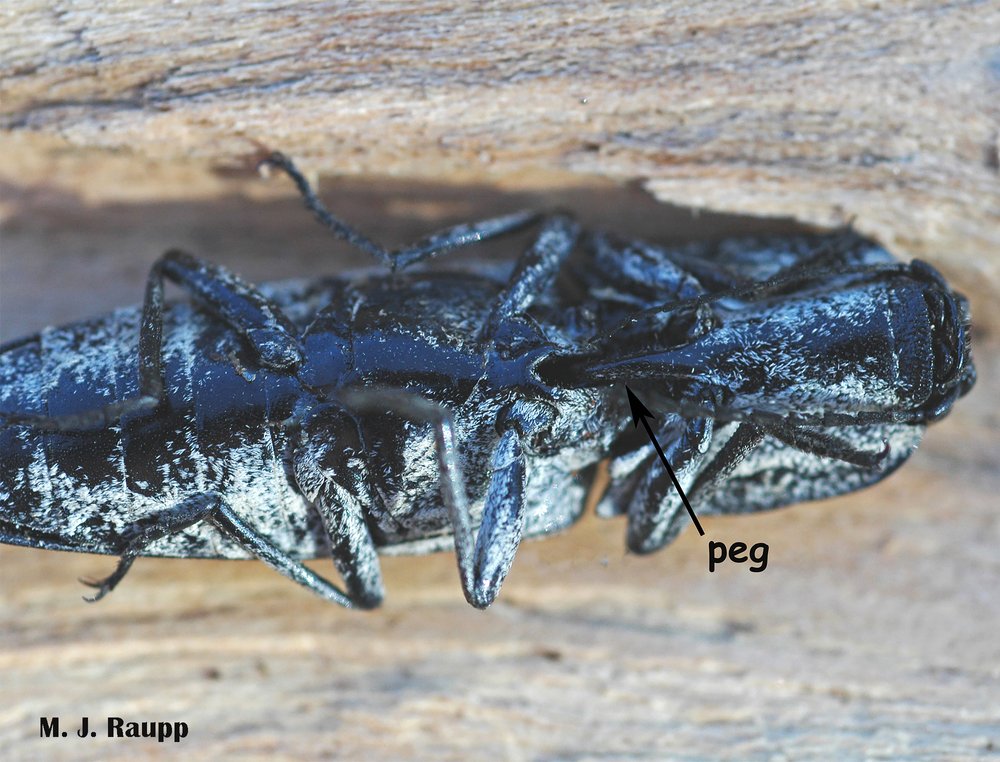

Walkingsticks are also known as stick insects or leaf insects in various parts of the world. Our local walkingsticks, northern walkingsticks like the one in our image, don’t quite measure up to those Asian giants, but at almost four inches these rascals are among the longest insects found in Maryland. They make their living eating foliage of trees and shrubs. In some years they are quite abundant and actually defoliate patches of trees, especially along rocky ridgetops. Although lacking the tough armor of beetles and evasive flight of butterflies, they have perfected the art of crypsis, that is, they have an uncanny resemblance to features of their environment. This ruse of looking like branches of the trees on which they feed helps them avoid detection by hungry predators.

Many phasmids rely on crypsis, the art of looking like a plant part such as a dead leaf or a twig, to escape the hungry eyes of predators. Giant Australian stick insects and Malaysian leaf insects look like dead or living leaves, respectively, while the large Vietnamese stick insects and Costa Rican stick insects look like, well, sticks! Other phasmids like the Floridian two-striped walkingstick and Chilean chinchimolle emit noxious chemicals from glands behind their head to deliver a nasty surprise to nosy predators.

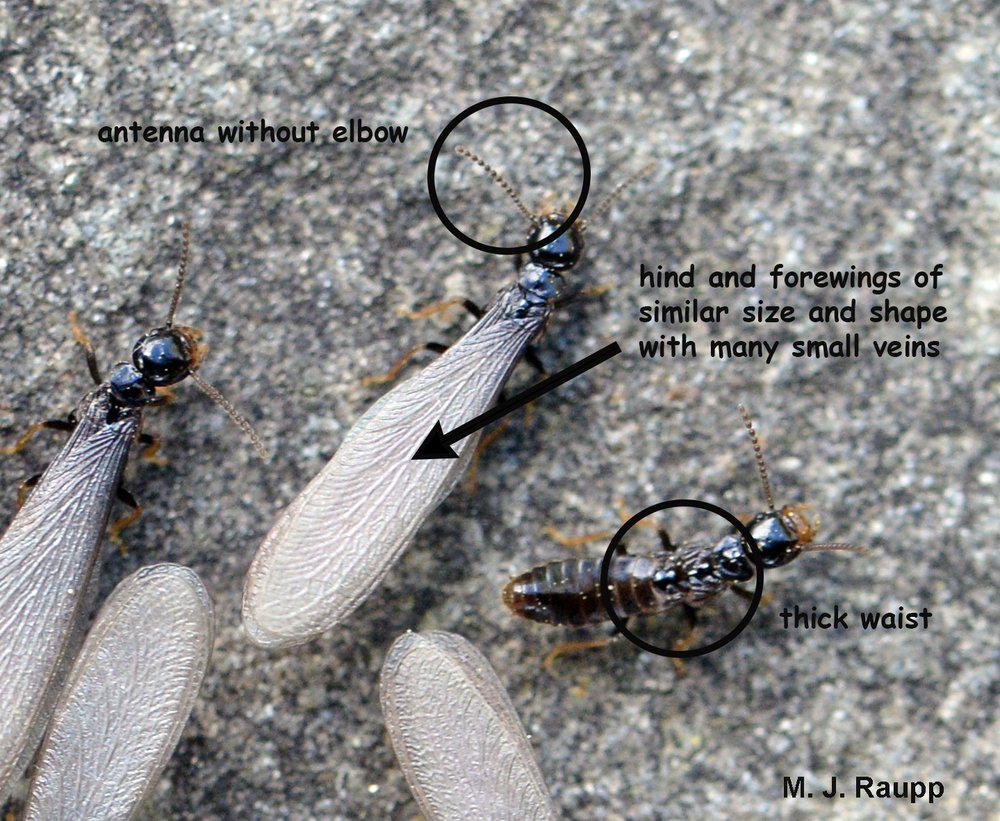

In addition to having greatly elongated body regions and appendages matching the colors and textures of twigs, walkingsticks move and pose in ways designed to fool sharp-eyed predators. As walkingsticks search for leaves, they sway slowly back and forth, mimicking the movement of a branch in the breeze. When not feeding or actively moving about, they assume a branch-like position with the front pair of legs extended directly forward. Their ability to hold an unflinching pose for hours is the envy of every mime. Unlike many adult insects, northern walkingstick insects never develop wings and nymphs and adults are quite similar in appearance. Some species of stick insects lay eggs on plants while others simply deposit them on the ground. For the northern walkingstick, winter is spent in the egg stage. A southern cousin of northern walkingstick, the two-striped walkingstick, is the longest insect in the United States and measures about half a foot. When camouflage fails to fool a hungry predator, walkingsticks may have another trick up their twig. Some species, including two-striped walkingsticks and elegant phasmatids, a.k.a. Chilean chinchimolles we met in previous episodes, have evolved glands on their thorax that emit foul-smelling, irritating chemicals to foil attacks by their enemies.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Larry Coy for providing the remarkable image of the northern walking stick featured in this episode. We also thank Dr. Audrey Grez of the University of Chile for identifying the chinchemolle. The following references were used in preparation of this episode: “4-Methyl-1-hepten-3-one, the Defensive Compound from Agathemera elegans (Philippi) (Phasmatidae) Insecta” by Guillermo Schmeda-Hirschmann, and “Defensive spray of a phasmid insect” by Thomas Eisner. Dr. Shrewsbury boldly modeled the rather large walking stick hair accessory in the Costa Rican rainforest.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week