West Nile Virus and other Fly Borne Diseases in the News – Beware of disease vectors: the Northern House mosquito, Culex pipiens, Asian Tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, and other biting flies

Hungry Northern House mosquitoes, vectors of West Nile virus, are thriving and on the hunt for blood.

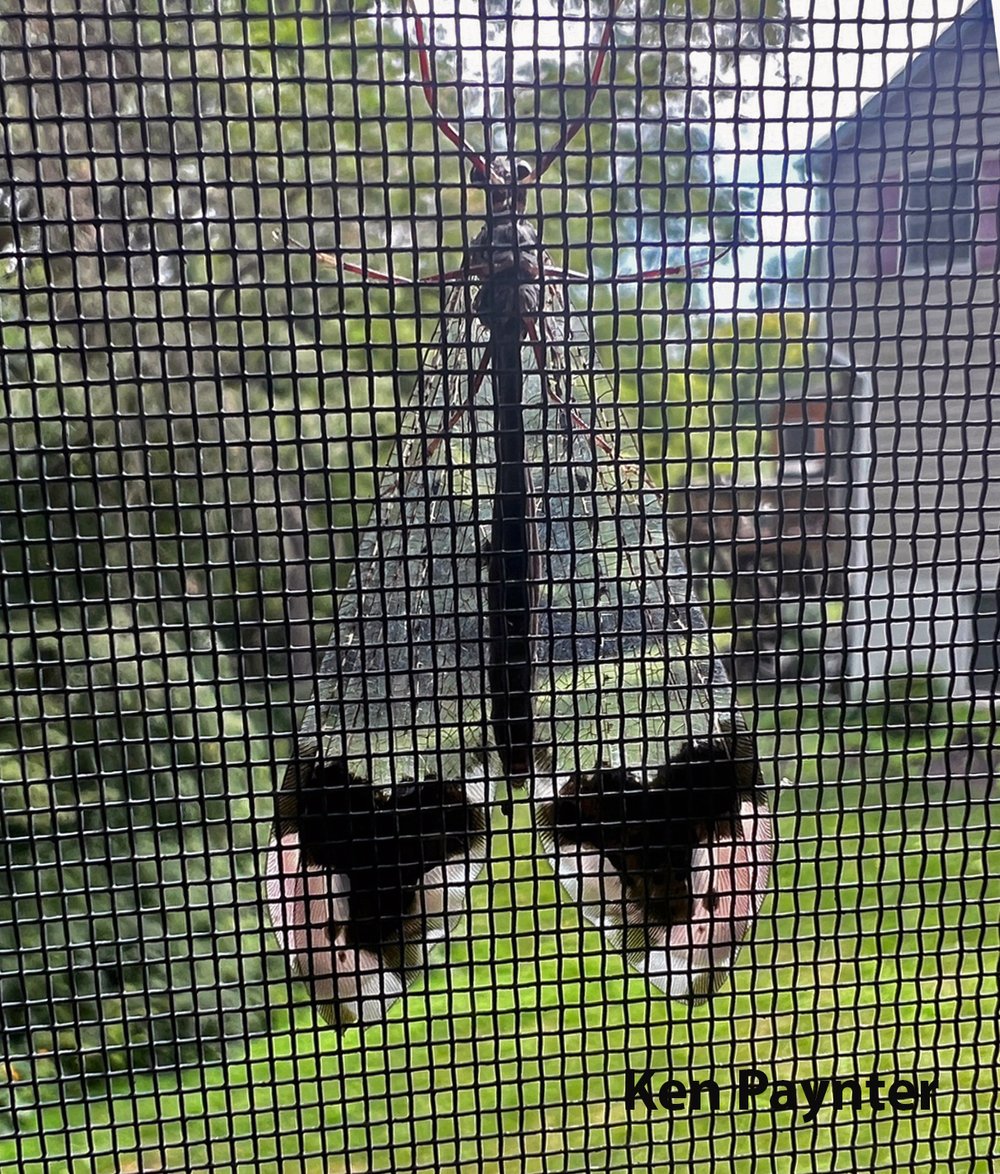

At only a few millimeters in length, tiny no-see-um midges can carry serious human viruses including the strange sloth fever virus.

Last week news agencies carried warnings about an uptick in mosquito borne diseases following reports that famed immunologist Dr. Anthony Fauci recently contracted and survived a bout of West Nile virus. As of August 27, 2024, 289 cases of West Nile virus in 31 states had been reported with Texas, Mississippi, and Nebraska leading the way. Even more disturbing was the recent demise of a citizen in New England from another mosquito borne illness, Eastern Equine Encephalitis. Recent travelers to Cuba have contracted another virus called sloth fever, a.k.a. Oropouche virus, carried by small biting flies called no-see-ums which we met in a previous episode. As record heat continues in our land, generation times shrink for mosquitoes. More mosquitoes are produced in shorter periods of time. Drenching storm systems create abundant breeding sites for aquatic mosquito larvae. Together, heat and rainfall provide the perfect storm for elevating populations of mosquitoes in many parts of our nation. Let’s learn a little more about mosquitoes, the risks they pose, and how to avoid their bites and the illnesses they carry.

Historically, September is the second most common month to contract West Nile virus. Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control

Mosquitoes are more than just a nuisance and several species carry important diseases such as West Nile Virus. According to the CDC, following its discovery in the United States in 1999, more than 59,000 cases of West Nile Virus have been reported and more than 2,900 deaths associated with West Nile Virus have occurred. While most of us shrug off West Nile virus with little or no symptoms, it can be severe and even lethal to seniors and certain others. Researchers have suggested that some seniors and people with compromised immune systems may lack sufficient immune responses to thwart the West Nile Virus.

Watch as a female Culex pipiens form molestus extracts all the blood she needs to produce the next batch of eggs and then scurries away to the shadow of a knuckle to hide. Filmed at twice life speed.

Asian tiger mosquitos are active during daylight hours. They vector important human diseases including dengue, chikungunya and Zika.

Many species of mosquitoes prefer to feed at dusk and you can avoid being bitten by staying indoors in the evening. However, unlike many of our native mosquitoes, the exotic Asian Tiger is a daytime biter, adding hours of itching, scratching, and swatting to days in the garden. Protect yourself from aggressive biters by wearing light-weight, long-sleeved shirts and pants when working outdoors. Certain brands of clothing are pretreated with mosquito repellents such as permethrin. I have worn these in tropical rainforests where mosquitoes were ferocious and they really did help. Many topical insect repellents can be applied to exposed skin before you go outdoors. Some will provide many hours of protection, while others provide virtually none. Some repellents should not be applied to children and you should always help kids apply repellents. Do not apply repellents containing DEET under clothing. To learn more about mosquito repellents, click this link to see repellents recommended by the Centers for Disease Control. For safety, be sure to read and follow the directions on the label of the repellent before you apply it to people or clothing.

If you dine outdoors, place a fan on your patio. The light breeze created by the fan will greatly reduce the number of mosquitoes flying and biting. Many traps are also available to capture and kill mosquitoes. Some rely on a light source to attract blood seekers. However, many types of moths, flies, and beetles are attracted to light. Mosquitoes, unfortunately, do not use light to find their meals and are NOT readily attracted to light traps. One study demonstrated that less than 1% of the insects attracted to light traps were biting flies such as mosquitoes. This study estimated that light traps kill billions of harmless and beneficial insects each year. Actually, blood seeking mosquitoes are attracted to odors emanating from the host. As we move about the earth, we release many odors, including carbon dioxide and lactic acid that are detected and followed by hungry mosquitoes to find us. Some mosquito traps release carbon dioxide and will attract and catch many mosquitoes. Female mosquitoes ready to lay eggs are attracted odors emanating from water sources. A clever trap called a Gravid Aedes Trap (GAT) has been used in community-wide programs in the DMV to reduce local populations of Asian Tiger mosquitoes. Females fly into these traps to lay eggs but never escape. Sounds like Hotel California for these tiny vampires.

Wheelbarrows and pails full of water? Dump them now! They are nurseries for mosquito larvae.

To reduce the chances of mosquitoes breeding around your home, eliminate standing water by cleaning your gutters, dumping your bird bath twice a week, inverting your wheelbarrow and getting rid of water filled containers. If you have an aquatic water garden or standing water on your property that breed mosquitoes, you can use a product containing the naturally occurring soil microbe known as Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis a.k.a. Bti. Bti comes formulated in doughnut-shaped tablets that can be placed in water to kill mosquito larvae.

A garbage pail lid full of water becomes the perfect nursery for a crop of Culex mosquitoes. Two egg rafts contain scores of eggs ready to hatch. Nearby, fleets of mosquito larvae called wriggles filter tiny particles of food from the water. In just a few short weeks, this lid will be bustling with fully developed wrigglers suspended beneath the water by breathing siphons. Amidst the milieu, zany mosquito pupae called tumblers bumble about. With continued hot weather and ample rainfall, adults will emerge, and yes, there will be blood.

With continued hot weather and ample rainfall, mosquitoes will be present for several more months. Be on the lookout and take precautions now to avoid being bitten.

Acknowledgements

Several interesting articles were consulted for this episode including “How the body rubs out West Nile virus” by Nathan Seppa, “Toll-like Receptor 7 Mitigates Lethal West Nile and Encephalitis via Interleukin 23-Dependent Immune Cell Infiltration and Homing by Terrence Town”, Fengwei Bai, Tian Wang, Amber T. Kaplan, Feng Qian, Ruth R. Montgomery, John F. Anderson, Richard A. Flavell, and Erol Fikrig, “Density and diversity of non-target insects killed by suburban electric insect traps” by Timothy B. Frick and Douglas W. Tallamy, and “Neighbors help neighbors control urban mosquitoes” by Brian J. Johnson, David Brosch, Arlene Christiansen, Ed Wells, Martha Wells, Andre F. Bhandoola, Amy Milne, Sharon Garrison & Dina M. Fonseca. Information on the geographical and seasonal occurrences of West Nile Virus came from the data rich CDC websites.

To learn more about the mosquitoes and how to defeat them, please view the following video, B.I.T.E. mosquitoes before they bite you!

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week