Cold weather arrives but don’t let your guard down for a tick attack: Blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis

On a warm day after Thanksgiving, I was surprised to see this blacklegged tick nymph embedded in my arm. Be vigilant when going outdoors on warm winter days.

In a behavior known as questing, ticks will climb high on vegetation and then with outstretched legs try to snare a victim on warm days in late fall, winter, and early spring.

Over the past several weeks we explored different strategies employed by insects to survive winter’s chill. Some migrate to warmer regions while others actually tolerate freezing or avoid freezing with cryoprotectants. A week or two ago, before the current arctic blast chased away daytime highs in the 60s and 70s, I received an almost fully engorged blacklegged tick from a friend. Fortunately, with confirmation that this ectoparasite was a blacklegged tick, my friend was able to begin a course of treatment to reduce the chances of contracting a tick-borne illness like Lyme disease. While many arthropods enter a state of arrested development called diapause in late autumn, others like our pathogen–toting nemesis the blacklegged tick are a bit more opportunistic. Some may enter diapause but others may be active on warmish winter days even when snow is on the ground. According to tick experts at the University of Rhode Island, “Blacklegged (deer) tick adults are not killed by freezing temperatures. Even in the coldest regions of North America, these ticks can still be active on days when temperatures are above freezing and they’re not covered over by snow.” A recent study in four Midwestern states found blacklegged ticks and other disease carrying species actively searching for a blood meal, a behavior called questing, on several days in January and February.

And in a classic case of “do as I say, not as I do”, last week after spending a couple of hours in a deer- laden forest near Antietam Battlefield, I awoke the next morning to find a partially engorged blacklegged tick nymph embedded on the inside of my left arm. Several past episodes of Bug of the Week have opined about ways to avoid being a meal for a tick, and quoting one, here is what I should have done before and after my jaunt in the woods:

“To reduce the risks of becoming a meal for a tick and the unfortunate recipient of alpha-gal, STARI, ehrlichiosis, or other tick-borne illnesses including Lyme disease, remember the word “AIR”. This stands for avoid, inspect, and remove.”

“A” – Avoid ticks and their bites in the following ways: When taking Fido for a walk, stick to the path, trail, or pavement. You are unlikely to encounter ticks on non-grassy surfaces. If you enter habitats where wildlife and ticks are likely to be present, such as grassy meadows, borders of fields and woodlands, and vegetation along the banks of streams, wear long pants and light-colored clothing. This will help you spot ticks on your clothes as they move up your body. Be a geek – tuck your pant legs into your socks. Pants tucked into socks force ticks to move up and over your clothes rather than under them where tasty skin awaits. Tuck that shirt into your pants as well. Apply repellents labeled for use in repelling ticks. Some are applied directly to skin, but others can be applied only to clothing. Don’t forget to treat your footwear, socks, and pant legs. Immature ticks, the rascally and hard to detect nymphs, are a key vector of diseases and these precautions will help prevent nymphs and adults from attaching to your skin. If repellents are used, be sure to read the label, follow directions carefully, and heed precautions, particularly those related to children. If your adventures take you into tick territory, consider placing your cloths directly into a clothes dryer rather than a hamper upon returning home. The heat of the dryer will kill hitchhiking ticks that might otherwise escape clothes in the hamper and cause trouble after your return home.

“I” – Inspect yourself, your family, and your pets thoroughly if you have been in tick habitats. Remember to do this when you return from the outdoors and when taking a shower. A thorough inspection may involve enlisting a helper to view those “hard to see” areas around back.

“R” – Remove ticks promptly if you find them. Removal within the first 24 hours can greatly decrease your risk of contracting a disease. If you find a tick attached, firmly grasp the tick as close to your skin as possible using a pair of fine forceps and slowly, steadily pull the tick out. Cleanse the area with antiseptic. The CDC and the Bug Guy do not recommend methods of tick removal such as smearing the tick with petroleum jelly or scorching its rear end with a match. Cases of some tick-borne diseases such as Lyme disease are the most common in children and seniors, so take special care to keep kids of all ages safe when they play outdoors.”

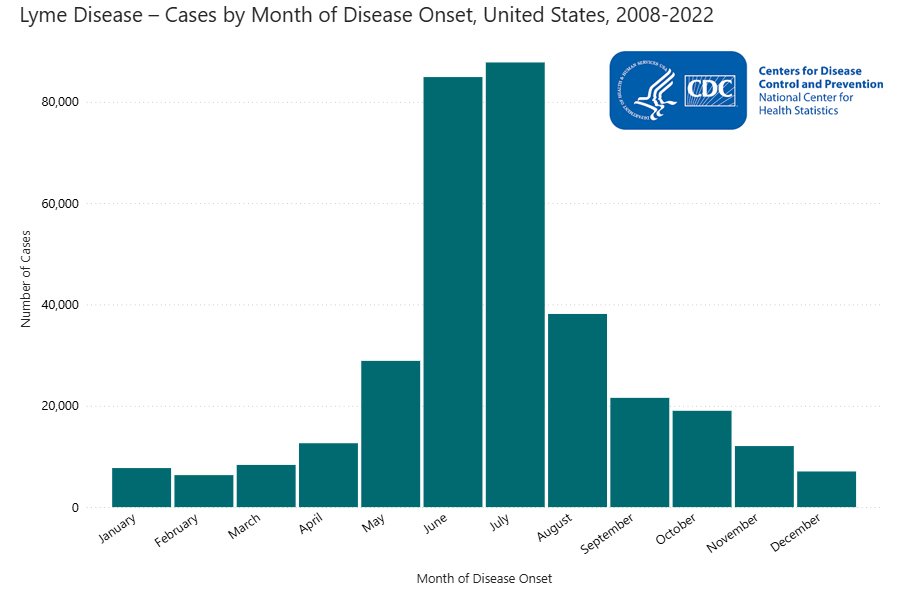

This great chart from the CDC demonstrates that tick borne illnesses like Lyme disease can be contracted during winter months as well as those in warmer seasons. Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Think ticks are done for the year? Think again. Warmer days in late autumn and winter mean ticks will be active during these seasons. Recently after a day in the field, I was surprised to find a blacklegged tick nymph embedded in my arm. Following unseasonably warm temperatures a short time ago, a friend sent me this almost fully engorged blacklegged tick. Blood in her grotesquely bloated abdomen will allow her to survive a feast-less winter and generate thousands of eggs to be laid next spring. Take precautions for avoiding tick borne illnesses by using tick repellents, putting cloths into the dryer when you get home, doing a tick inspection of people and pets, and removing ticks promptly if you have been in tick territory outdoors. If you have a tick, remove it, get it identified, and share this information with your physician to help avoid a serious illness.

This fully engorged tick is likely to survive winter’s chill here in the DMV and turn her blood-filled abdomen into thousands of eggs which will be laid next spring.

As winter temperatures rise during this period of climate change, we can expect ticks to be active on more days in late autumn, winter, and early spring. Be vigilant when you venture outdoors. Despite a morning low of 28 degrees Fahrenheit, today’s high is predicted to reach a balmy 40-some degrees, maybe warm enough for ticks to quest for a blood meal. Later today, when I work in the same deer-infested forest, I will follow the mantra of “AIR” and try to prevent another bodily incursion by the dreadful blacklegged tick.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Anne Marie for sharing her engorged tick and Dr. Shrewsbury for removing a tick embedded in my arm. The following interesting references were consulted to prepare this episode: “Winter Tick Activity” by The University of Rhode Island (anonymous), and “Unexpected winter questing activity of ticks in the Central Midwestern United States” by Ram K. Raghavan, Zoe L. Koestel, Gunavanthi Boorgula, Ali Hroobi, Roman Ganta, John Harrington Jr., Doug Goodin, Roger W. Stich, and Gary Anderson.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week