Life underground and the vanguard arrives, Hail Brood X, 2021 in Maryland! Magicicada spp.

The vanguard of Brood X periodical cicadas seen on a garden fence in Towson, Maryland last week serves notice that the main event is just a few weeks away. Photo credit: Tano Arrogancia

Before we hail the arrival of the first Brood X cicadas to emerge in Maryland, let’s answer a few frequently asked questions that have popped up repeatedly over the last few weeks. Several viewers and journalists have asked what periodical cicadas have been doing underground for the last seventeen years. Often this query is linked to a related ask about cicadas hibernating for seventeen years. Actually, periodical cicadas have been busy feeding and growing, albeit at a relatively slow pace, ever since they entered the ground in 2004. Yes, in a somewhat COVID-like existence, they have social distanced in subterranean chambers, not to halt the spread of disease, but likely to avoid competing with other cicadas feeding on tree roots. Although they are not the longest lived insect (some termite queens may live over 50 years), at 13 or 17 years as youngsters, periodical cicadas are purported to have the longest juvenile period of any insect.

Adding one more mystery to this magical creature is its strange pattern of youthful development. Immature cicadas are rightly known as nymphs rather than larvae. Larvae are the immature growth stages of insects with complete metamorphosis that have a pupal stage, like beetles, butterflies, bees and several other taxa. Cicadas have incomplete metamorphosis and skip the pupal stage, instead going through several nymphal stages. After hatching from an egg inserted into a tree branch by its mother, a tiny hatchling cicada known as the first instar nymph tumbles to earth and quickly dives underground. In the soil it locates a small root and taps into a vascular tissue, called xylem, where the nymph acquires nutrients and water by imbibing xylem fluids. Clever studies of cicada life underground by Chris Maier revealed surprising development patterns of periodical cicadas. This first nymphal stage of a 17-year cicada usually lasts only a year before it sheds its skin (a.k.a. exoskeleton) and graduates to the second instar nymph. However, after the first year, life in the remaining four stages of a nymph may vary dramatically. Dr. Maier discovered that second instar nymphs were found over a period of six years, third instar nymphs were distributed over eight years, fourth instar nymphs were found over ten years, and fifth and final instar nymphs were found over a seven-year period. Here is the amazing part, despite the apparent disparate and asynchronous rates of development, all of these youngsters managed to emerge from the earth in synchrony in year 17, right on schedule. This mystery is yet unsolved. What about 13 year cicadas? Well, they also scramble across the years at varying rates of development, only faster than the 17-year crew, and they too manage to emerge in synchrony.

In 2004, tiny cicada nymphs the size of a rice grain tumbled to earth, buried themselves, and began feeding on roots of plants. After shedding their skin a few times, they were the size of a jellybean several years later. By year fourteen they had grown to almost one inch in length. Now cicadas are peeking out of the soil and putting the finishing touches on exit holes before they emerge. Soon the jailbreak will be underway as they dash to vertical structures to shed their skins and head to the treetops.

This early riser also appeared last week in Rockville, Maryland after emerging from a flower pot of soil brought indoors for a couple of days. Indoor temperatures likely hastened its emergence from the soil. Photo credit: Cicada Safari

In a world underground, devoid of light and visual cues, how do periodical cicadas keep track of the years? One hypothesis has it that the annual fluxes of xylem fluids and compounds contained therein may allow cicadas to track the passing of years. In winter when deciduous trees have no leaves, a dramatic reduction in liquids flowing in xylem tissue takes place. In spring when leaves burst forth and transpiration draws water from the roots to leaves in the photosynthetic canopy, xylem pressure changes again. Perhaps, these fluxes are the annual cues to which cicadas “listen.” Another hypothesis not entirely independent from the aforementioned is that a yet unknown molecular clock ticks away the years somewhere within the tiny mind of the cicada in much the same way some dastardly circadian rhythm wakes me at 5:30 am irrespective of when my alarm is set. In addition to the long-term synchronization mentioned above, there is a short-term synchrony, a biological starter’s pistol that signals it is time to make a jailbreak from the earth in year 13 or 17. When soil temperatures reach a temperature of about 64 degrees Fahrenheit, it marks the time in spring when the world above ground is warm enough for cicadas to make a mad dash for a vertical structure, shed their juvenile skins, become adults, ascend trees, best fierce predators, fly to the treetops, make a wonderful, raucous chorus to woo their mates, and for the males, find that special someone willing to be the mother of his nymphs.

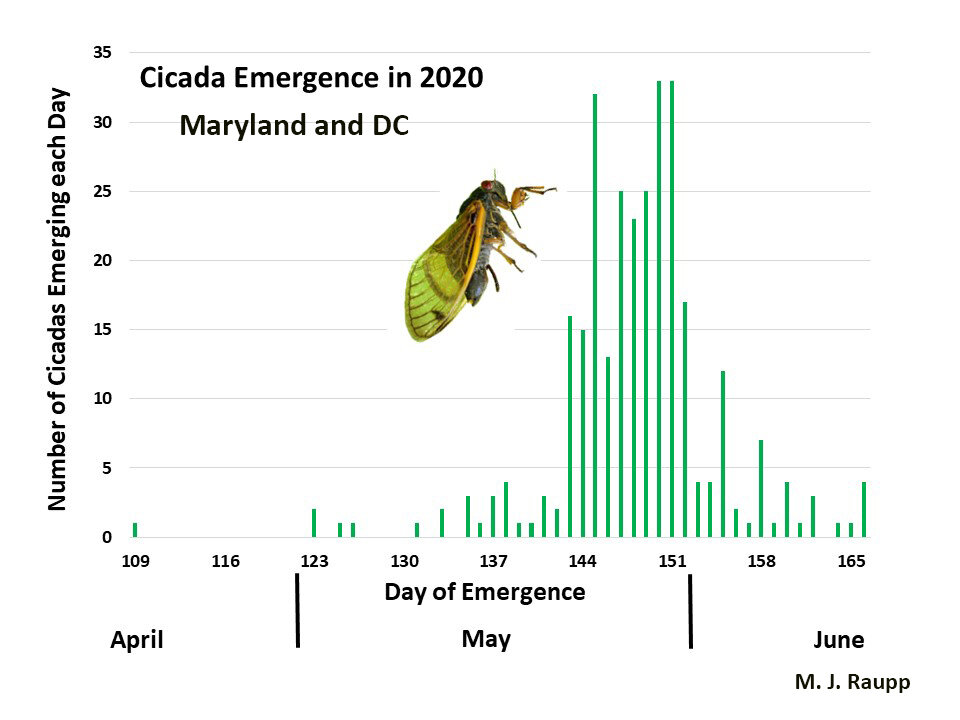

Brood X cicadas appearing one year early in the spring of 2020 provide clues as to when cicadas will appear in 2021 in Maryland and DC. The first cicada to emerge was seen on April 19 and the last on June 14. If 2021 is anything like 2020, outliers will appear in April, but the great cicada tsunami hits the last two weeks of May. By Memorial Day weekend the cicadapalooza will be rocking the treetops here in the DMV. Graph credit: Michael J. Raupp

This week the vanguard of periodical cicadas appeared in Towson and Rockville, Maryland. The sighting of a periodical cicada in Towson on April 19, 2021 falls within a day of a similar sighting of another periodical cicada near Towson in 2020. A second sighting occurred in Rockville on April 23 of a cicada that emerged in a home from some potting soil that had been brought inside two days earlier. No doubt a couple days of cozy temps inside probably sped up its development, but these two sightings confirm that the cicadapalooza is just around the corner. Cicada-philes, before you get too excited, please look at the graph that accompanies this episode. Here in the DMV the great cicada tsunami is most likely to arrive from the middle to the end of May. With temperatures expected in the 70s and 80s this week, don’t be surprised if a few more early risers appear. Keep your eyes open.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Jennifer and Tano Arrogancia, Gene Kritsky, and the Cicada Safari for sharing images of Brood X cicadas and providing the inspiration for this episode. The following references where used to prepare this story: “The ecology, behavior, and evolution of periodical cicadas” by K. S. Williams and C. Simon, “Thermal synchronization of emergence in periodical “17-year” cicadas (Homoptera, Cicadidae, Magicicada)” by J. E. Heath, “Combining Data from Citizen Scientists and Weather Stations to Define Emergence of Periodical Cicadas, Magicicada Davis spp. (Hemiptera: Cicadidae)” by M. J. Raupp, C. Sargent, N. Harding, and G. Kritsky. Gene Kritsky and Cicada Safari provided data used for the graphic of cicada emergence in 2020. We also thank Chris Simon for sharing her lecture notes of cicada development underground, Chris Maier for his studies of cicada biology, and John Cooley for enlightening discussions.

To learn more about periodical cicadas, please visit the Cicada Crew website at the University of Maryland.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week