What lies beneath the wax? A duo of leaf-eating sawflies: Dogwood sawfly, Macremphytus tarsatus, and Butternut woollyworm, Eriocampa juglandis

Beautiful dogwood sawfly caterpillars assume their characteristic curly pose between bouts of defoliating dogwoods.

During a recent conversation with a Master Naturalist over some holes in leaves of ornamental mallows, I shared my inability to find one of the usual suspects associated with shredded mallow leaves, the mallow sawfly, a wasp we met in a previous episode. My rather public response elicited a flurry of rejoinders from gardeners and naturalists whose dogwoods were ravaged this year by another member of the sawfly clan, called the dogwood sawfly. Sawflies are primitive members of the bee and wasp order of insects known as the Hymenoptera. Unlike their kin, who either feast on the flesh of other arthropods or dine on nectar and pollen of plants, several families of sawflies feed on leaves. So this week seems to be a good time to catch up with a couple of fascinating leaf-munching sawflies.

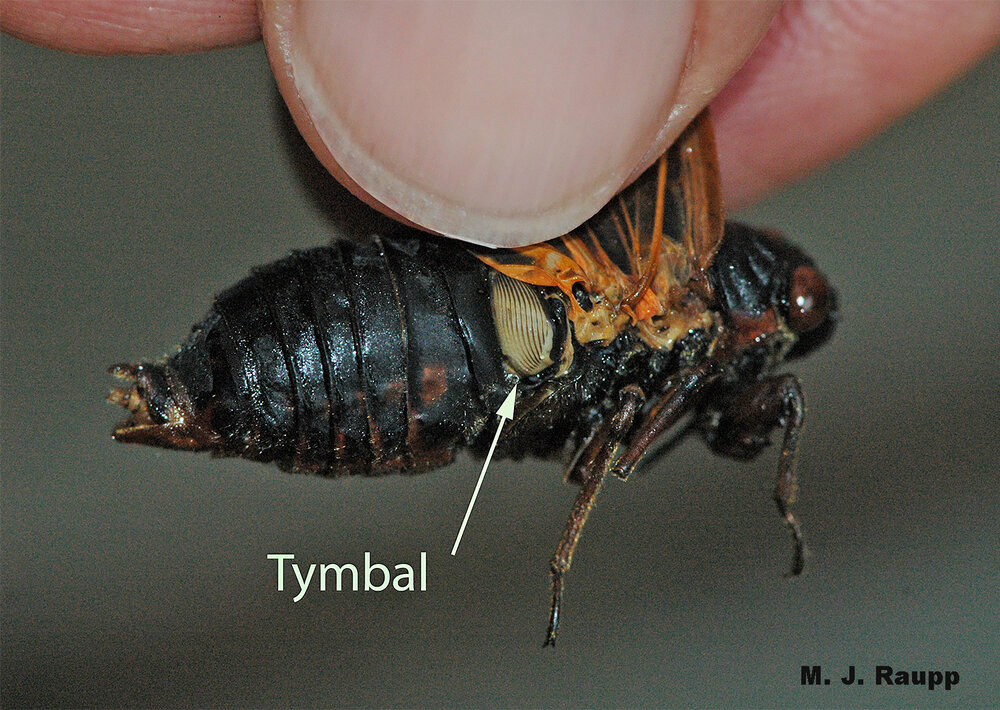

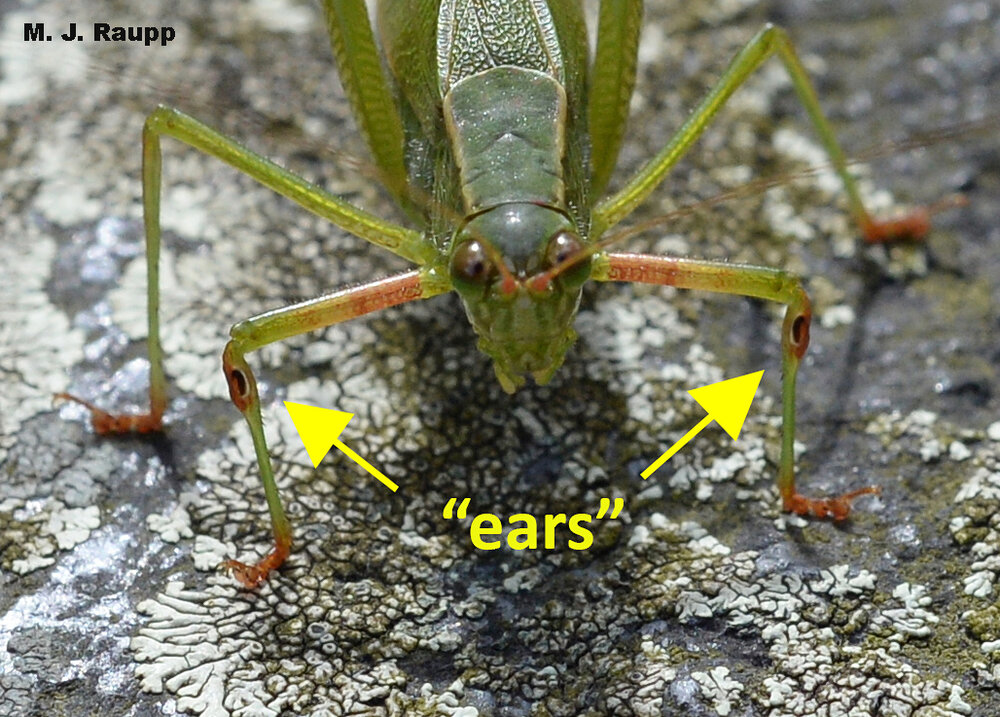

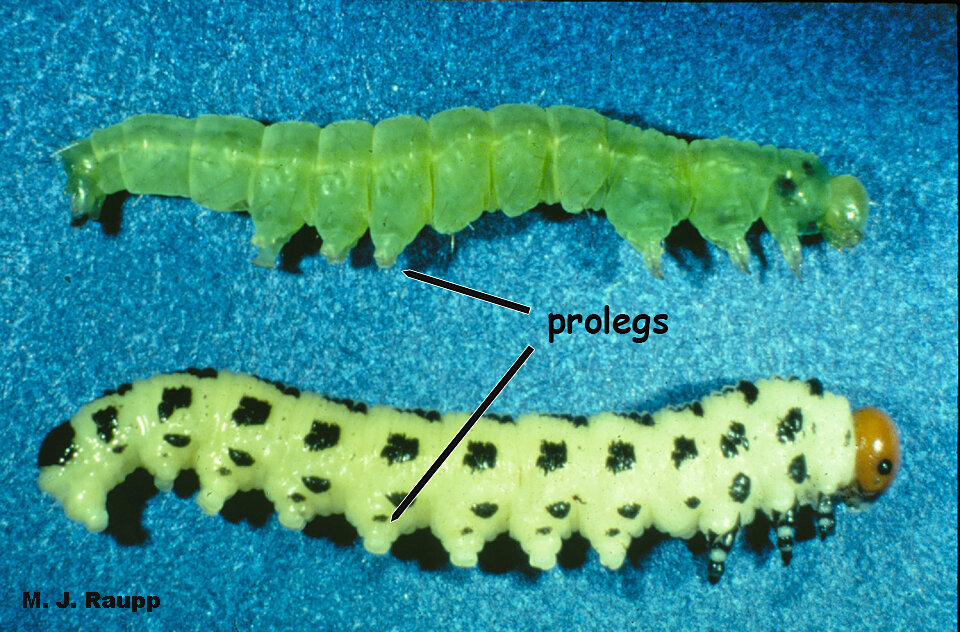

An easy way to tell the difference between caterpillars, the larvae of moths and butterflies, and sawfly larvae is to count the pairs of appendages called prolegs on their abdominal segments. Caterpillars like the larva on top have five or fewer pairs of prolegs. Sawfly larvae like the one below usually have six or more pairs of prolegs.

Let’s start with dogwood sawfly. One of the favored hosts of dogwood sawfly is grey dogwood, Cornus resemosa, but silky dogwood, Cornus amomum, and flowering dogwood, Cornus florida, are also on the menu. Winter is spent as a larva ensconced in a chamber built in rotting wood or sometimes structural wood, including siding. In spring larvae pupate and later, from May through July, adults will emerge to fly and find mates. Females deposit eggs on the undersurface of dogwood leaves in clutches numbering 100 or more. Eggs hatch and larvae consume leaf tissue and develop through summer. With the approach of autumn and imminent leaf drop, large sawfly larvae wander from dogwood trees to construct overwintering redoubts in wood. Although many sawfly larvae bear a striking resemblance to caterpillars, the larvae of moths and butterflies, most can be distinguished from Lepidoptera larvae by the number of pairs of appendages called prolegs found on abdominal body segments. In addition to three pairs of jointed walking legs on the thorax, most caterpillars have five or fewer pairs of fleshy prolegs on their abdominal segments. By contrast, in addition to the requisite three pairs of thoracic legs, most sawflies bear six or more pairs of prolegs.

Snaky dogwood sawfly larvae practice their curls beneath a leaf while an almost fully developed larva waves to the camera while searching for another meal.

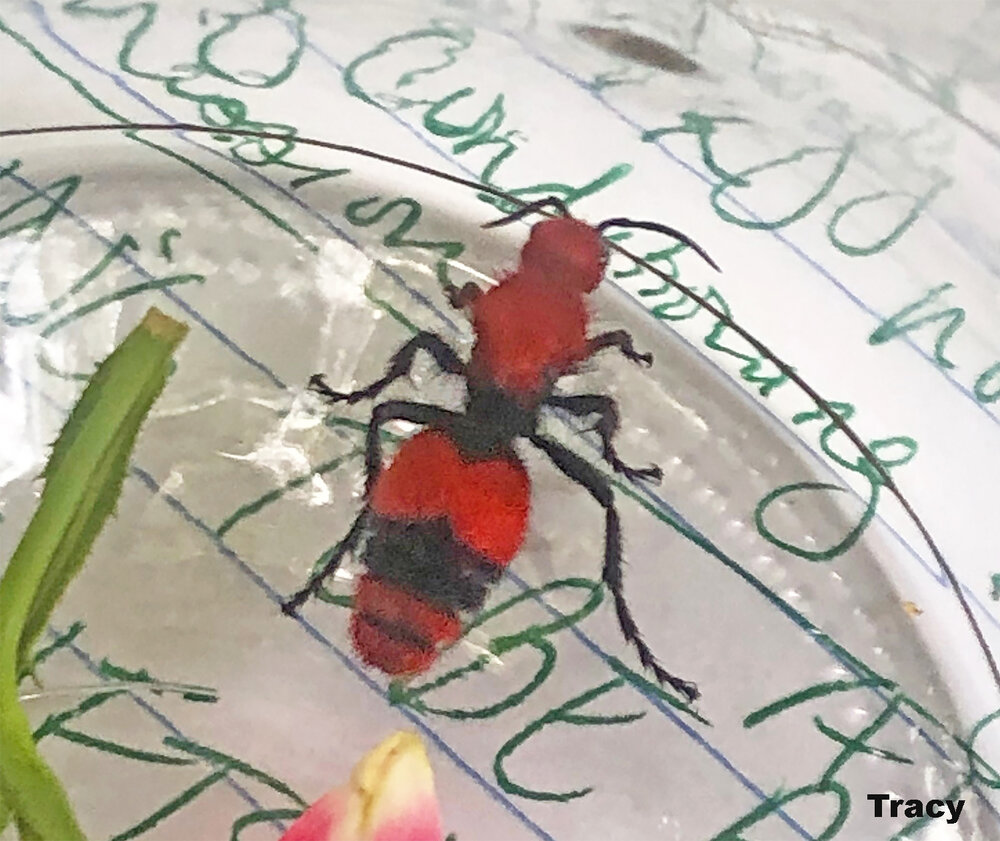

As larvae, dogwood sawflies have, quite literally, a colorful juvenile history. After hatching from eggs, larvae are rather translucent yellowish creatures resembling gummy worms. As they develop and molt, specialized glands produce a snowy-white cloak of wax. Fully developed larvae shed the white waxy cloak and assume a dashing color scheme of yellow, white, and black. Why the chameleon routine? Well, some scientists have speculated that the brilliant white coloration and elongated body of young larvae may mimic a bird dropping and reduce the chance of predation. What self-respecting bird eats bird droppings, right? Another hypothesis suggests predators and small parasitic wasps may be unable or unwilling to effectively attack sawfly larvae through their cloak of wax.

Last week while on an adventure along the Patuxent River, I spied what I believed was a larva feeding on a patch of dastardly stilt grass. Delighted that something might be eating this aggressive invader, I investigated the critter and was disappointed to find nothing but an empty exoskeleton adorned with tufts of fluffy wax. Above the stilt grass towered a lovely black walnut tree whose leaves were disappearing down the gullets of another sawfly known as the butternut woollyworm. Unlike its cousin the dogwood sawfly, this sawfly spends winter as a pupa in the soil enclosed in a durable case. In spring adults emerge and, after mating, females use their saw-like egg-laying appendage called an ovipositor to insert eggs into the mid-vein of walnut leaves. Newly hatched larvae are naked but soon develop a flocculent cloak of magnificent white wax. Upon molting from one instar to the next, this cloak is shed but often remains attached to a leaf for several days or falls on underlying vegetation like stilt grass to fool passing entomologists. In addition to black walnut, Juglans nigra, as their common name implies woollyworms also frequent butternut, Juglans cinerea, and have been reported from hickories, Carya spp. Over the next week or two, be on the lookout for these waxy sawflies on dogwoods and trees in the walnut family. Try to imagine what all the wax is about.

High in the canopy, butternut woollyworms dine on leaves of a black walnut tree. Although their white waxy mane evokes visages of a shaggy dog or Cousin Itt, the flocculent cloak may dissuade attack by predators or parasitoids. White, waxy filaments dancing in the breeze may not advertise a tasty meal to vertebrate predators accustomed to naked caterpillars for dinner.

Acknowledgements

This episode is dedicated to our friend Jimmy and in memory of Angela who shared their sawflies and inspired this Bug of the Week. The interesting articles “Be Alert for Dogwood Sawfly” by Joe Boggs, Insects that Feed on Trees and shrubs by Warren Johnson and Howard Lyon, and “Seasonal Cycle and Habits of the Butternut Woollyworm” by L.L. Hyche were consulted in preparation of this episode.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week