Just in time for Halloween, spooky spiders invading homes! Wolf spiders, Lycosidae

In a basement room, a mother wolf spider carries dozens of spiderlings on her back until they are old enough to fend for themselves.

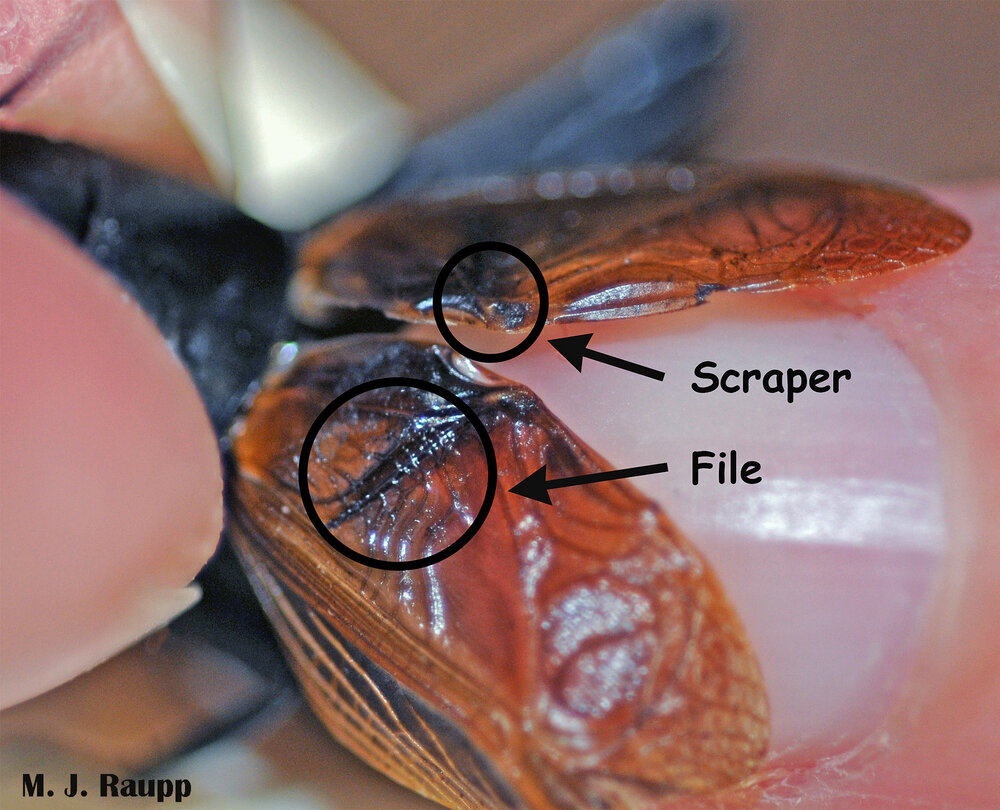

Last week we visited fall field crickets, whose autumnal home invasions provide cheerful chirps useful in estimating temperatures without a thermometer. Over the past few weeks several inquiries have arrived about a different kind of home invader, spiders. Our home has been graced by smallish wolf spiders dashing across the bedroom floor, cruising the bathroom, slipping in the sink, and audaciously reclining on the bed. What’s up with this?

Beautiful wolf spiders tote their egg cases to reduce chances of their young falling victim to predators or parasitoids.

Wolf spiders are among the most important invertebrate predators providing the ecosystem service of biological control by devouring caterpillars, leaf hoppers, lace bugs, and just about anything else they can sink their fangs into. As generalist predators, they eat a broad range of prey and are vitally important in putting a beat-down on insect pests not only in agricultural ecosystems, but also in residential gardens and landscapes. During this growing season as I tended my flower beds and vegetable gardens, as in previous years, I was amazed and pleased at the abundance of wolf spiders dashing through the mulch and hiding beneath stones. As summer wore on, female wolf spiders were regularly seen toting their dazzling white egg cases slung beneath their abdomen. By late summer and early autumn after these eggs hatched, busy mothers toted scores of tiny spiderlings upon their backs, safe from hungry jaws of other ground-dwelling predators.

Big hairy tarantulas can be spooky, as can the wolf spider with its ghoulish fangs devouring hapless prey. Over the last few weeks wolf spiders have invaded my home. Small spiderlings provide morning surprises on the bathroom floor, in the sink, and sometimes on furniture. But these wolf spiders are not to be feared. They are highly beneficial predators of many pests in our gardens and landscapes. Consider catching them in a cup, glass, or other container and freeing them outside away from the house where they will help eliminates pests in your landscape next growing season.

I often liken these voracious invertebrate predators to large meat-eaters like lions, apex predators sitting high atop food webs. To me, wolf spiders are the clear sign of complex and functional garden food webs. An inquisitive neighbor recently asked “Ok, if there is a smorgasbord of excellent food items outside, why do spiders come inside in autumn?” Great question, because my home probably has a bug or two but nothing compared to my garden. A possible explanation lies here. Our resident spider expert explained that as autumn wanes, the bounty of spider prey declines dramatically outdoors as insects and other invertebrates hide in hibernal redoubts or migrate to warmer latitudes. With declining sources of food, these wandering hunters are forced to travel farther to find a meal. Their search may bring them to homes and other structures where faulty door-sweeps, caulking, or weather-stripping allow them to enter and deliver spooky morning surprises.

Spiders and their webs get really big the week before Halloween.

Spider invasions might be terror for arachnophobes, but for bug geeks close encounters of an arachnid kind provide an opportunity to hone one’s spider catching skills. Here’s what we do. Using a drinking glass or, better yet, a dedicated green plastic spider-catching cup, we chase down and corral these rascals. Often, we simply use a hand to usher the spider into the cup, but if touching spiders is not your thing, a tissue or piece of paper may help you guide them into their holding cell. Once captured and admired, they are released outdoors to fulfill their spidery roles of hunting pests in the garden. Of course, closing gaps with caulk and weather-stripping and replacing faulty door sweeps will not only help exclude spiders, but with Old Man Winter just around the corner, these easy home improvements will also help keep those heating bills down.

Happy Halloween from Bug of the Week!

Acknowledgements

We thank spider-loving Ashley and the inquisitive crew of the Weather Channel for providing inspiration for this episode. Dr. Jeff Shultz provided interesting insights into these home invasions, and the fascinating review “Spiders as biological control agents” by Susan Reichert and Tim Lockley provided background information.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week