How are you doing, Class of 2021? Brood X Magicicada spp.

Peeking out from his escape tunnel, this little Brood X periodical cicada nymph will soon join billions of his brood mates above ground for a boisterous party in the treetops.

During the past month, Bug of the Week’s peregrinations have visited Chilean chinchemolles, Peruvian beetles, Costa Rican arachnids, and Floridian tiger moths. This week we hop-scotch a thousand miles north to the DMV to check on the progress of Brood X periodical cicadas. During the past several weeks the Cicada Crew at the University of Maryland has been busy reassuring journalists and the public at large that, yes indeed, Brood X cicadas a.k.a The Great Eastern Brood, will appear in 15 states and the District of Columbia in the eastern half of the USA this spring. While issuing these claims, a little voice whispers something like “What if climate change or some yet unknown manifestation of the insect apocalypse has intervened in the last 17 years and cicadas don’t appear?”

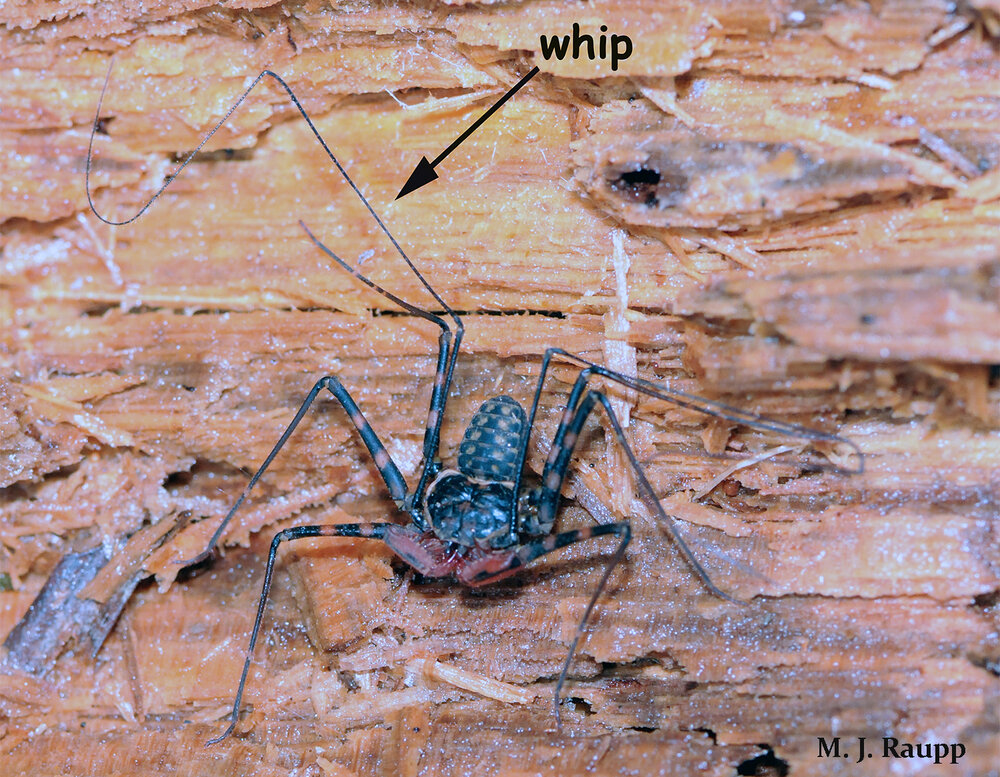

To quell a bit of rising panic that prognostications of a spectacular cicada-palooza might prove false, last week we visited our favorite Brood X cicada patch to see how those rambunctious teenage cicadas were doing. The first strike of the shovel unearthed a fully grown cicada nymph. Already under construction was his escape tunnel, the passageway from the realm of darkness where he sipped xylem liquid from the roots of plants for the last seventeen years to the world of light where he will join legions of brood mates in a rambunctious mating game. This discovery is strikingly similar to a dire account published in the Annapolis gazette on April 3, 1751. An anonymous colonist wrote the following “We are informed … in some Places the Locusts have been found in great plenty, just under the surface of the Earth, almost at their full growth. May God avert our impending Calamities!” This ominous report most likely refers to Brood XIX, a brood of thirteen-year cicadas found in what is now St. Mary’s County, Maryland, the former colonial capital of Maryland and still an important agricultural center 270 years after this account.

Seventeen years ago in the spring of 2004, periodical cicadas laid eggs in treetops. In summer, the eggs hatched and tiny nymphs tumbled to earth and burrowed down to feed on tree roots for the next seventeen years. Fast forward to 2021. Brood X periodical cicadas are now poised to exit their subterranean crypts and make a boisterous entry to the world above ground.

So, if you are concerned that periodical cicadas may not show this spring, put your fears to rest. In parts of Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia, the vanguard of Brood X periodical cicadas will make their presence known in a month or so. We will explore much more about these remarkable creatures in upcoming episodes.

Acknowledgements

The wonderful book “Periodical Cicadas: The Plague and the Puzzle” by Gene Kritsky, and the source of all things cicada, the Cicada Mania website, were used as references to prepare this episode. To learn more about Brood X periodical cicadas in Maryland, visit our 2021 Cicada Brood X information clearinghouse at https://cicadacrewumd.weebly.com/

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week