Rhode Island is known for its hundreds of miles of New England coastline, fresh seafood, charming villages, vibrant art scenes, and miles of trails. From historic homes to bustling cities, “Little Rhody” has no shortage of things to do, see, and experience.

Unfortunately, a diverse population of insects is among the list of things residents will experience. With various service locations in Rhode Island, Catseye Pest Control has first-hand experience with some of the unique insects that homeowners and businesses encounter. We also have the equipment and expertise needed to eliminate these common Rhode Island bugs.

Ants

Ants are the most common pest across the country, and Rhode Island is no exception. Fortunately, out of more than 12,000 species in existence, only about 25 typically infest homes and businesses. Two common ants that invade homes in Rhode Island include carpenter and odorous house ants.

Carpenter Ants

Carpenter ants are large and may bite when threatened. More problematic is the carpenter ant’s preference for tunneling into dead and damaged wood. They can live in wall voids, attics, crawlspaces, and other areas. Because they live inside wood, you may not see live ants, but you may notice piles of sawdust and insulation near nest entrances.

Odorous House Ants

When threatened or crushed, these ants release a strong blue cheese-like scent as part of their defense mechanism. They often nest under toilet seats, inside dishwashers, inside wall voids, or anywhere that is warm and close to water. Although they don’t sting, bite, or damage structures, they can contaminate food.

Ticks

Ticks are dangerous parasites related to arachnids like spiders and mites. They feed on the blood of humans, pets, and other animals. Not only are they notoriously tricky to spot until they start feeding, but they can also spread serious diseases like Lyme disease and Colorado tick fever. Tick prevention and awareness are vital for keeping people and pets healthy.

Deer Tick

The deer tick, also called a blacklegged tick, typically feeds on deer. These ticks can spread Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and babesiosis. These reddish-brown pests frequent wooded areas like trails and forests but can be found anywhere deer roam.

Dog Tick

The American dog tick is reddish-brown with light yellow or white markings. Although these parasites prefer feeding on dogs, they can also feed on humans. Dog ticks spread tularemia and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, an illness that causes rash, fever, and other symptoms.

Lone Star Tick

Although the Lone Star tick was once more common in the Southern United States, it has made its way into New England and the Northeast. This tick has a characteristic white spot on its back. A bite from a Lone Star tick can cause Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness (STARI), characterized by an expanding rash. These ticks may also carry Ehrlichiosis, which causes fever and muscle pain. Bites can also trigger an Alpha-gal allergy, which can cause a serious allergic reaction from eating foods like pork and beef.

Bed Bugs

Bed bugs are a problem throughout New England and across the country. These small blood feeders hitch a ride on clothing, luggage, and upholstered items. Once they reach indoor spaces, bed bugs find dark, out of the way crevices to nest in and only come out to feed. Common areas where these pests nest include the seams of mattresses and box springs, the underside of wall hangings, the folds of curtains, and along the crevices in baseboards.

Cockroaches

Although it’s rare, cockroaches can actually bite humans. The larger problem, however, is that these pests are a health hazard that spread germs and can trigger allergic responses. Cockroaches have existed for thousands of years and can be notoriously challenging to eliminate.

American Cockroaches

One of the larger species found in Rhode Island, the American cockroach has a reddish-brown body that is up to 1 1/2 inches long. They hide in shady areas and eat meat and plants. These cockroaches can easily contaminate food sources, counters, floors, and other areas and can cause digestive illnesses. American cockroaches can also trigger an allergic reaction in people sensitive to their droppings or skin shedding.

Oriental Cockroaches

These cockroaches are among the few outdoor scavengers that have a strong drive for water. They often can be found in bacteria-laden areas like sewers and trash zones with decomposing food, making them dangerous sources of contamination. Oriental cockroaches are black or dark brown with bodies about 1 inch in size.

German Cockroaches

German cockroaches have wings but rarely fly, preferring to stay in low, concealed spots. They have small, tan, or light brown bodies with two vertical stripes and average 1/2 inch in size. These cockroaches prefer staying together in groups and are known for emitting a musty scent that can mimic a moldy smell.

Flies

This buzzing pest can be downright dangerous because it can carry organisms that cause serious diseases like typhoid fever, dysentery, and anthrax. Different types of flies enjoy different habitats and food sources. Some of the most common types include the house fly, fruit fly, and gnats.

House Fly

People sometimes call the common house fly a “filth” fly in a nod to its love of organic matter (both decaying and fresh) and the likelihood of it spreading diseases. House flies have characteristically loud buzzes, red eyes, and bodies with four black stripes.

Fruit Fly

These tiny terrors affect people worldwide on every continent, except Antarctica. Fruit flies don’t bite humans, but they can be irritating. They feed on organic matter — not just in fruit bowls but also in the garbage. Fruit flies have small tan bodies and are challenging to spot until they appear in large groups.

Gnats

Gnats look a lot like fruit flies but with black bodies. They don’t bite humans or pets, but they feed on decaying plant matter and plant roots and can transmit pathogens to plants that humans eat. Infestations are common in greenhouses and in over-watered potted plants. Eliminating these pests typically requires allowing the soil to dry out, which, unfortunately, could also kill the plant.

Mosquitoes

Whether you’re hitting the beach, taking a hike, or relaxing outdoors, protecting yourself and your loved ones from the itchy bites of mosquitoes is a must. These buzzing insects can spread diseases, including West Nile Virus and Eastern Equine Encephalitis. Wearing loose-fitting clothing and using EPA-registered insect repellents can be helpful. Additionally, removing sources of standing water in outdoor spaces can help reduce mosquito breeding grounds.

Spiders

Rhode Island’s spiders may look scary, but many are beneficial to outdoor spaces because they eat other insects, which helps naturally control pest populations. The common house spider can grow up to 5/16 inch and has a body in colors ranging from brown to off-white. You may also encounter one of the following spiders in the state:

Bark Crab Spider

With coloring that resembles tree bark and a sideways walk that looks similar to a crab, this arachnid makes it easy to understand how it got its name. Its black body sports cream-colored or tan speckles and a flat, wide abdomen. Bark crab spiders eat insects and can be found in wooded areas and parks.

Arrow-Shaped Micrathena

This colorful orbweaver spider spins intricate webs and has a distinct, triangular-shaped body. Females have sharp spines on their abdomens and typically have red bodies with bright yellow on the abdomens. Males are usually black with white around the edges. These spiders are venomous to other insects but harmless to humans.

Eastern Harvestman

The Eastern harvestman is an arachnid that looks like a spider but doesn’t have fangs or venom. They use their long legs to move around and to help them sense their surroundings. The Eastern harvestman has a dark, round body that lets it easily blend into the environment. It can spray a strong-smelling component from its first pair of legs as part of its defense system.

Black Widow Spider

Black widow spiders aren’t usually a significant problem in New England, but they have been spotted here in Rhode Island. The black widow is renowned for its strong venom, painful bite, and females’ habit of biting and killing their mates.

Termites

These Rhode Island bugs are more than just a nuisance — termites can cause widespread destruction to properties. The most common species found in Rhode Island is the eastern subterranean termite, which thrives in moist, dark environments. Termites can be difficult to find and require professional intervention to eliminate them.

Other Unique Rhode Island Bugs

From ladybugs to “assassins,” the Ocean State contains some of the most remarkable bugs and insects found in New England.

Cow Killer Ants

Also commonly called “red velvet ants,” these insects aren’t ants at all but a type of wasp. Females don’t have wings, which gives them an appearance that resembles huge red and black ants. Males have wings and look more like a wasp. These insects have powerful, painful stings and lay their eggs inside beehives. When the eggs hatch, young cow killer ants eat the bumble bee larvae inside the hive.

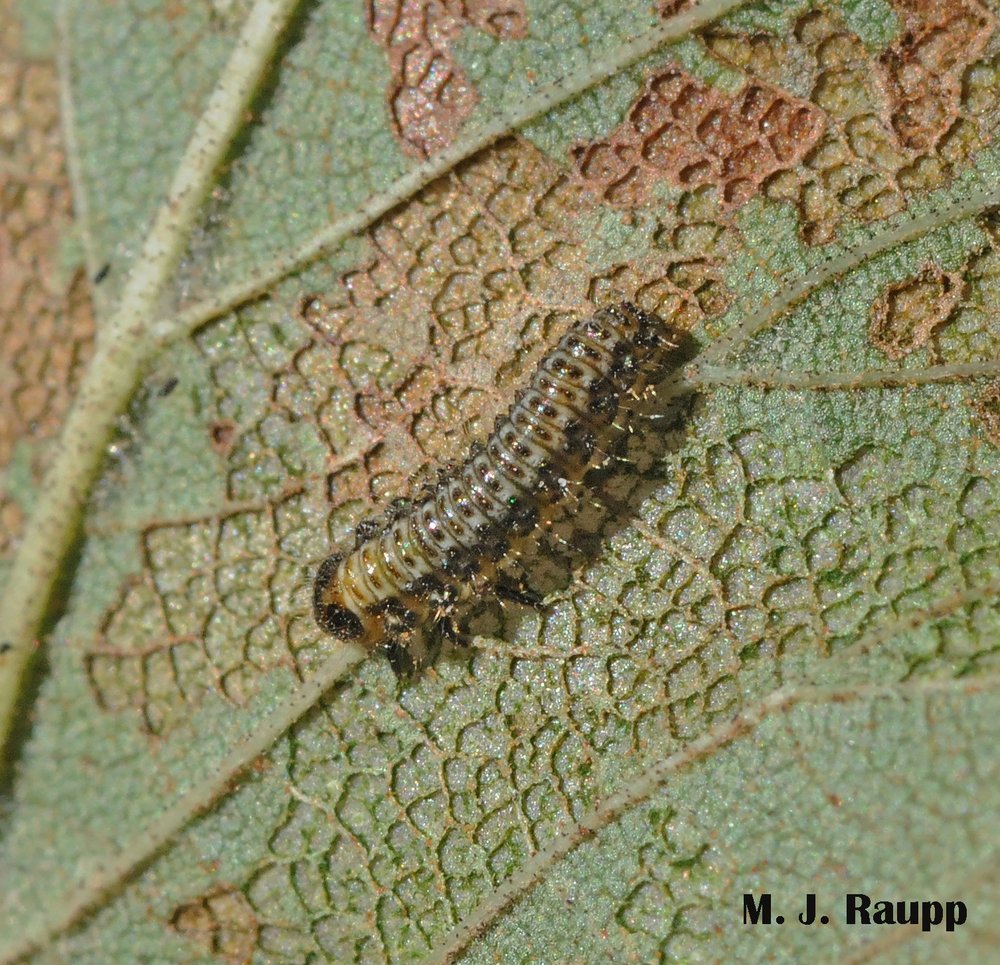

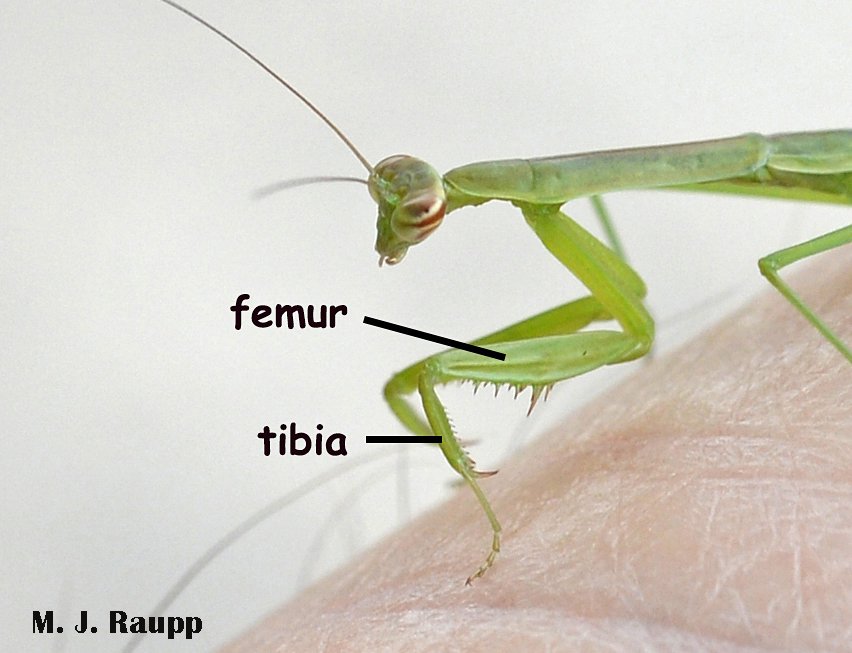

Assassin Bugs

This category of insects contains about 200 different species, with bodies ranging from brown or gray to black, orange, yellow, and red. Assassin bugs have six legs and narrow heads, and they prey on other insects. They can be beneficial outdoors, but they have sharp beaks and painful, venomous stings that don’t discriminate.

Wheel Bugs

This type of assassin bug has a spiny, wheel-shaped back and a vicious looking fang on top of its head. Wheel bugs use their fangs to stab their victims multiple times. Although they typically feed on insects, wheel bugs can also stab humans with their fangs.

The Masked Hunter

Another species of assassin bug, the masked hunter has a painfully strong fang that it can use to repeatedly stab anything — or anyone — that gets in its way. Young masked hunters are covered in sticky hairs that get coated in dirt, dust, and lint, making them look like a creature from another planet. This insect’s primary diet consists of bed bugs, so seeing masked hunters typically signals a bed bug infestation.

Evergreen Bag Moth

Not a worm at all but actually a type of moth, these pests create bags from silk and plant foliage. From Providence to Barrington and beyond, these moths cause significant damage to host trees, which include arborvitae, juniper, pine, sycamore, maple, and cedar. Females don’t have wings and look similar to grubs, while males are dark, winged, and hairy. When a young bagworm caterpillar lands on its host, it attaches to it, with only its head and thorax emerging as it moves.

American Pelecinid Wasp

Despite its fearsome appearance, the American pelecinid wasp doesn’t sting. Females use their long, tail-like abdomens to deposit eggs on the backs of underground grubs. When the eggs hatch, the young wasps burrow inside the grub and use it as a food source.

Beetles

Some beetles carry toxic substances, while others can infect plants with diseases or damage them. With more than 450 species of ladybugs, they are among the more common beetles in Rhode Island. In addition to these dome-shaped beetles with shiny red, orange, or yellow bodies, the state is also home to many other types of beetles. The calligrapha beetle looks similar but has calligraphy-like swirls on its yellow, orange, brown, white, or gray body. Antelope beetles feed on rotting wood and look formidable with their large, wide heads and long pinchers.

Stink Bugs

Although these smelly pests are sometimes confused with beetles, stink bugs belong to the halyomorpha family, known as “true” bugs. They have a shield-like back and are typically brown or green. These insects eat vegetation, including popular crops like tomatoes and apples. Stink bugs often move indoors when the weather gets cold and are harmless to people. However, they do release a characteristic odor that is not pleasant.

Best Ways to Prevent and Control Pests in Rhode Island

Knowing what to look for is only part of the solution. Prevention and control vary widely from pest to pest, but residents can typically follow various standard recommendations for all pests. Keeping foliage trimmed back from buildings, keeping food neatly stored, and securing garbage are important practices for reducing the risk of pests making their way indoors.

However, the best way to keep homes, businesses, and other establishments pest-free is with routine preventive treatments and professional pest control. Catseye Pest Control’s Platinum Home Protection is the best defense against pest damage and dangers. This comprehensive program is customized for each client. We provide pest removal, seal gaps and cracks, apply environmentally safe pest deterrents around the perimeter, and more. With bi-monthly follow-ups and our 100% service guarantee, this protection offers the ultimate peace of mind.

Contact Catseye Today

Whether you have caught sight of some creepy crawlies or you simply want to prevent any pests from invading, Catseye can help. Our trained, licensed technicians will perform a thorough inspection inside and outdoors before creating a custom plan to keep your property pest-free. Schedule an inspection of your Rhode Island home or business today to get started.

The post Bugs Found in Rhode Island appeared first on Catseye Pest Control.

This article appeared first on Catseye Pest