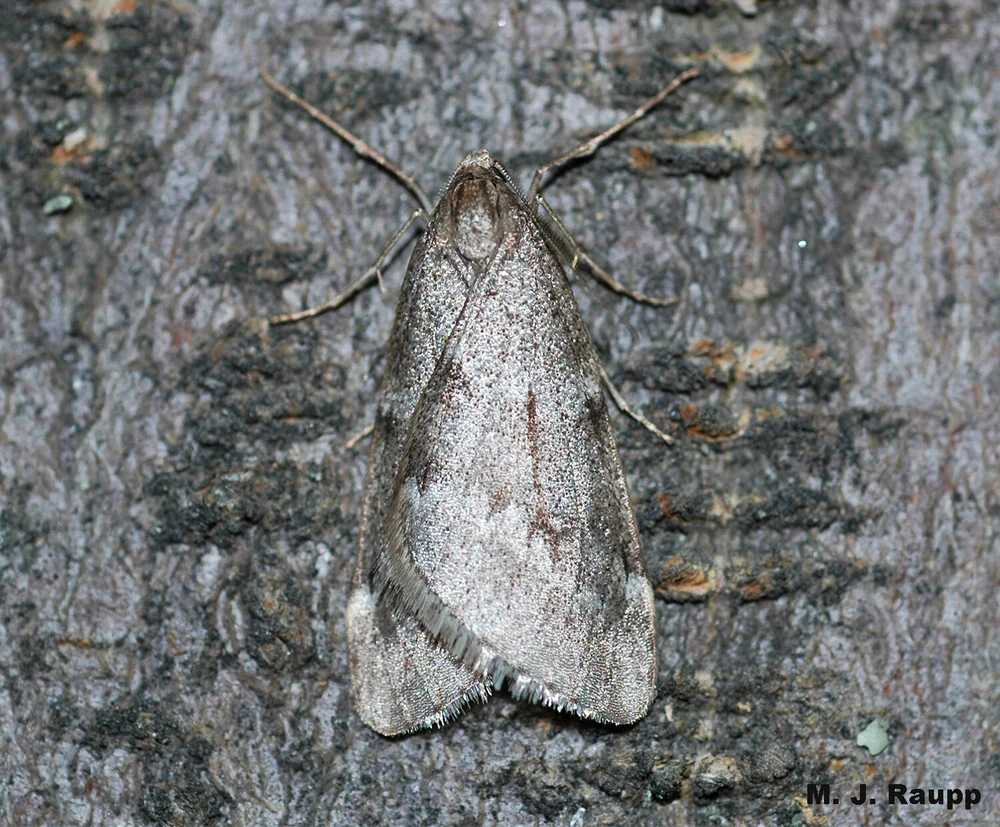

Wintry appearance of a strange moth: Fall cankerworm, Alsophila pometaria

Wingless, flightless, non-feeding, winter-active, what a strange moth is this female fall cankerworm.

Flight-capable male fall cankerworms are often seen on mild winter nights resting on trees or near porch lights.

Last year was spectacular for moths and butterflies. We visited many beautiful butterflies including brush-foots and swallowtails, and several marvelous moths such as silk moths and webworms. One of the more curious members of the moth clan, fall cankerworm, made its presence known on a blustery day last week. This enigmatic creature defies several “norms” found in the rest of the moth coterie. As you know, most moths are winged creatures that frequent the skies on summer nights as they search for mates and suitable plants on which to lay their eggs. However, female fall cankerworms are wingless. They have forgone their ability to fly. Is this some unfortunate twist of fate or the curse of a malevolent sylvan fairy? Perhaps, but many entomologists believe that wingless cankerworm moths have found a clever way to leave behind more offspring. By shifting precious bodily resources from equipment needed for flight, such as wings and muscles to flap them, and redirecting these resources to the production of eggs, female cankerworms may be able to bring more little caterpillars into the world and enhance their lineage’s odds for survival.

High in the treetops fall cankerworms deposit eggs on the bark of branches and twigs.

Regardless of the reason that underlies the mystery of the wingless moth, they are a wonder to see. Beginning in late autumn, adult fall cankerworms emerge from pupal cases in the soil. Females move from the soil and climb vertical structures such as trees and buildings. Shortly after sunset, on milder winter nights, female moths release a chemical signal called a sex pheromone that attracts male moths. Fall cankerworm males have functional wings and are good fliers. Each male tracks the pheromone to its source and the chilly couples mate. After this interlude, females climb high into the tree and place their eggs on the bark of small branches and twigs. Females do not live to see their offspring. Unlike other species of moths that have tubular mouthparts used to sip nectar, the female fall cankerworm lacks functional mouthparts. She cannot feed and shortly after depositing her eggs she dies.

Shredded leaves left behind by hungry caterpillars give these pests their common moniker, cankerworm.

The larvae of fall cankerworms hatch early in the spring soon after the buds of trees open and young leaves appear. Caterpillars of fall cankerworms and other members of their clan are also known as inchworms. They have multiple legs on their front and rear ends. By alternating their grasp between front and rear legs and bending their body upward into a loop, they move along twigs and leaves as if measuring the world an eighth of an inch at a time. The name cankerworm derives from the shredded, cankered mess caterpillars make as they consume foliage of trees. Their larvae reach phenomenal numbers in some locations and years, and may devastate many shade trees such as oaks, maples, elms, and lindens. We learned more about the ravages caused by this native pest in a previous episode of Bug of the Week. In addition to the fall cankerworm, other members of their clan such as spring cankerworm and linden looper, are active in the winter and have flightless females. A close relative of the fall cankerworm called the winter moth has recently appeared in cities and suburbs in New England, where it has become a perennial pest wreaking havoc on several species of shade trees in those areas.

On a bright winter day an adult fall cankerworm tries to ignore the annoying thumb of a bug geek. Can you guess why cankerworm caterpillars go by the name inchworms?

On a bright but chilly winter day visit a maple, elm, or oak and try to catch a glimpse of these strange ladies as they escape their earthly confines and slowly ascend trees in search of suitable repositories for their eggs.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week