Beetles roasting on an open fire: Roundheaded borers, Cerambycidae; Flatheaded borers, Buprestidae; and Darkling beetles, Tenebrionidae

Darkling beetles huddle beneath the bark of a log to escape winter’s chill.

With the return of chilly wintery weather, it’s time to split a few logs for the fireplace. As you wield your axe or maul, take a few moments to peel back the loose bark on some logs. You might be surprised by what you find. If your firewood is not too old and punky, just beneath the bark you may find serpentine galleries that wend their way along the surface of the hard wood. Examine the inner surface of the bark and you will see the mirror image of this trail. Galleries like these are often created by beetle larvae called roundheaded borers and many of my maple logs were chuck full of these wood-eaters. After completing development beneath the bark, they chew a round hole to the outside of the log and emerge as a longhorned beetle, so named for the remarkable length of their antennae.

It’s easy to see how Asian Longhorned Beetle got its name. Just look at those antennae.

Many species of roundheaded borers like the ones tunneling through my maple logs prefer to eat the tissues of dying or dead trees. Some like the dreaded Asian Longhorned Beetle attack living trees with a preference for those under stress. This beetle is responsible for the death of tens of thousands of trees in New York, Chicago, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Ohio since its introduction to the United States in the 1990’s. Roundheaded borers that eat wood have powerful jaws to chew their way through hard plant tissues. We met other longhorned beetles in a previous episode as they dined on nectar and pollen. If you bring firewood into your home and store it for an extended time before you use it, you may be treated to the emergence of several wonderful longhorned beetles, maybe just in time for the Holidays!

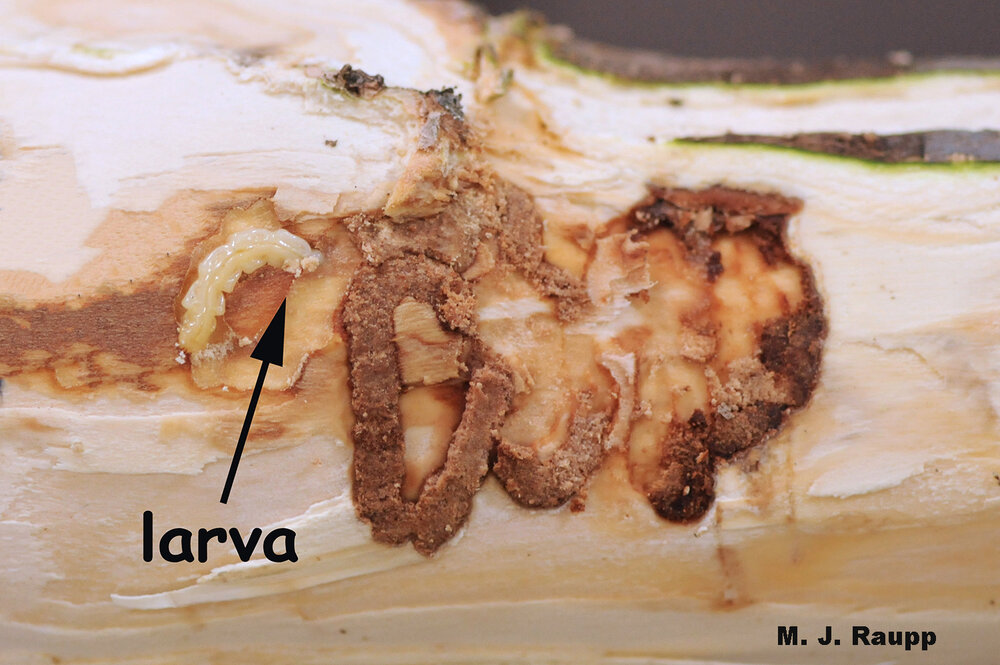

Looking like a sleepy Jabba the Hutt beneath the bark of my firewood, a roundedheaded borer wriggles in its gallery. After completing development, it becomes an adult longhorned beetle, so named for its exceptionally long antennae similar to those of the stunning locust borer.

As I peeled back the lose bark of a second maple log, I discovered a bevy of darkling beetles. Darkling beetles spend the winter in a frigid scrum beneath the bark of trees awaiting the warmth of spring to resume their activities. Most darkling beetles feed on plant material of some sort – living or decaying. Not far from where the adult darkling beetles huddled, several darkling beetle larvae moved at a glacial pace through the decaying wood beneath the bark. Like their roomies, the roundheaded borers, darkling beetle larvae complete their development when the warmth of spring returns.

Just under the bark, an Emerald Ash Borer larva has almost completed its development. A frass filled gallery marks its progress through the wood.

In addition to maple logs, I have a great store of ash firewood thanks to the nefarious Emerald Ash Borer that has killed more than a million ash trees since its introduction to North America some two decades ago. And as I split some of the ash logs, what to my wondering eyes should appear, but an almost fully developed larva of the Emerald Ash Borer. This little rascal will complete its development under the bark next spring and emerge in May as a gorgeous adult beetle known as a metallic wood boring beetle.

Classic D-shaped exit hole of a flatheaded borer, in this case the Emerald Ash Borer.

The Emerald Ash Borer larva is called a flatheaded borer. It too makes sinuous galleries beneath the bark, but upon emerging from the tree the adult leaves behind a tell-tale exit hole in the shape of the letter “D.” Get it, D has a flat side and so does the hole made by a flatheaded borer. Entomologists are pretty clever, eh?

A beautiful but deadly Emerald Ash Borer battles a giant finger before flying away. It is one of many metallic wood boring beetles that attack and kill trees.

So, during this most wonderful time of the year, on a wintry night when you are sitting in front of the fireplace singing the songs you love to sing and watching the chestnuts pop, pop, pop, listen carefully: those might not be chestnuts popping.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week