Death to aphids: Brown ambrosia aphid, Uroleucon ambrosiae and other assorted aphids meet flower fly larvae, Syrphidae

Amidst a horde of brown ambrosia aphids, a syrphid fly larva attacks its next victim. M. J. Raupp

One of the best performers in my flower bed is a raucous native plant known as cup plant, Silphium perfoliatum, a premier attractor of insects to the garden. Extravagant floral displays provide nectar and pollen to wide variety of flies, bees, butterflies, and wasps. Nutrients coursing through vascular vessels support several species of sucking insects including leafhoppers, treehoppers , and aphids. And where there are abundant juicy prey items, there are predators, lots of them. During spring and early summer, populations of brown ambrosia aphids have exploded on my cup plants. Like many of their kin, in spring and summer these gals are parthenogenic. They are an all-female society reproducing without the assistance of males. As aphids feed, they excrete a waste product called honeydew. Honeydew contains volatile organic compounds (VOCs), the aromas of which act like a dinner bell ringing “come and get it”. The more aphids and honeydew on a plant, the more likely it will be discovered by flower flies. Once the infestation is detected, the females fly lays a small white egg near the colony of aphids. The egg hatches into a wriggling larva (a.k.a. maggot) whose sole purpose is to hunt and eat soft-bodied prey. With no true eyes, this blind assassin discovers its victims by swinging its head to and fro, searching for prey with sensory structures located on the front end of its fleshy head. When it bumps into an aphid, the flower fly larva snares the aphid with its mouth hook [it looks like Captain Hook’s hook]. Mouthparts pierce the aphid’s cuticle, and the larva sucks the aphid’s blood.

When in bloom, cup plants are dynamite attractors of pollinators. But pre-bloom, cup plants often generate fantastic populations of brown ambrosia aphids. Volatile odors released by the aphids serve as a dinner bell for squads of hungry predators and parasitoids. Not long after aphid populations exploded, adult flower flies deposited eggs near colonies of aphids. From these eggs hatched fierce larvae laser focused on hunting and eating aphids night and day. Watch as one of these tiny terrors makes short work of a misguided aphid. The flower fly larva snares the aphid with its mouth hook. It looks like Captain Hook’s hook. It then pierces the aphid and sucks out its blood. Flower fly larvae make short work of aphids on plants. Along with gangs of spiders, lady beetles, lacewing larvae, predaceous midge larvae and parasitic wasps, aphids on my cup plants will soon be history.

It’s easy to see why another name for the flower fly is hover fly. Flower flies deposit white eggs like these near colonies of aphids. Eggs hatch and blind flower fly larvae hunt by casting their head two and fro. Prey like this aphid are snagged with a mouth hook. Once captured the contents of the aphid are consumed. Sometimes hapless aphids blunder into fly larvae. You can see the dorsal heart of the larva beating as it feeds. Little wonder that aphid populations can collapse when flower flies and other predators and parasites arrive.

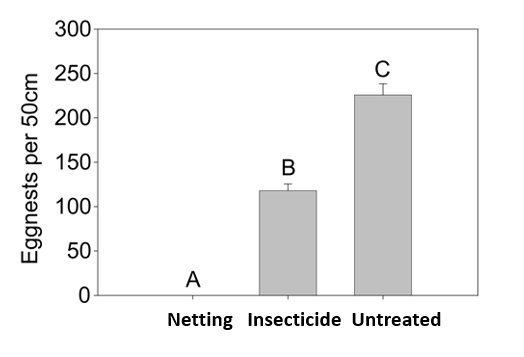

Flower fly maggots have prodigious appetites. In the laboratory, I have watched these predators consume more than 25 aphids in a day. Reports of aphid carnage in the literature puts the casualty figures at more than 200 aphids during development for each maggot. In some agricultural systems, flower flies are believed to provide 75% to 100% control of aphids. In my experience with aphids, flower flies, with a little help from lady beetles and other predators, can entirely wipe out populations of aphids in a matter of weeks. So, before you reach for the aphid spray, carefully look to see if the maggot brigade and company are at work. While the brown ambrosia aphids put a minor beat down on my cup plants, they are generally good news for my garden. The aphids have become a factory for many species of predators including spiders, lady beetles, lacewing larvae, predaceous midges and parasitic wasps that will move to other plants in my landscape once the brown ambrosia aphids are kaput, all part of Mother Nature’s plan for a more sustainable landscape.

This little Cycloneda lady beetle has her jaws wrapped around a juicy brown ambrosia aphid. M. J. Raupp

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jeff Shultz for identifying the cool male lynx spider and Dr. Paula Shrewsbury for planting silphium, identifying the pretty polished lady beetle and providing inspiration for this episode. The fascinating account of defensive behaviors in aphids entitled “Collective Defense of Aphis nerii and Uroleucon hypochoeridis (Homoptera, Aphididae) against Natural Enemies” by Manfred Hartbauer was consulted to prepare this episode.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week