An STD in cicada land has cicadas behaving strangely: Magicicada spp. and Massospora cicadina

Massospora turns the cicada’s abdomen into a fungus garden.

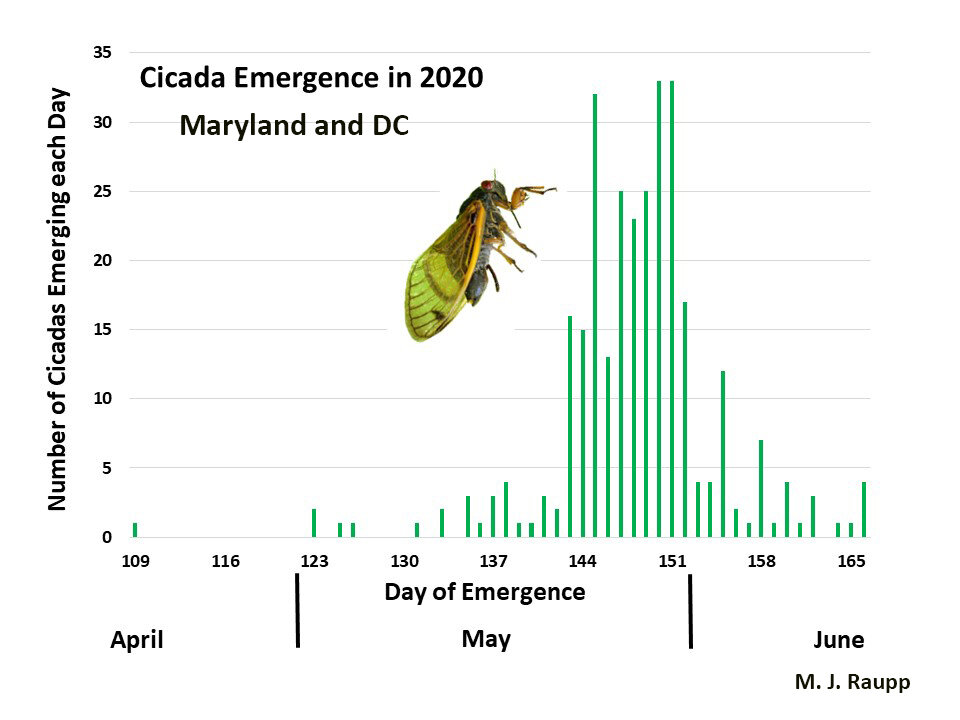

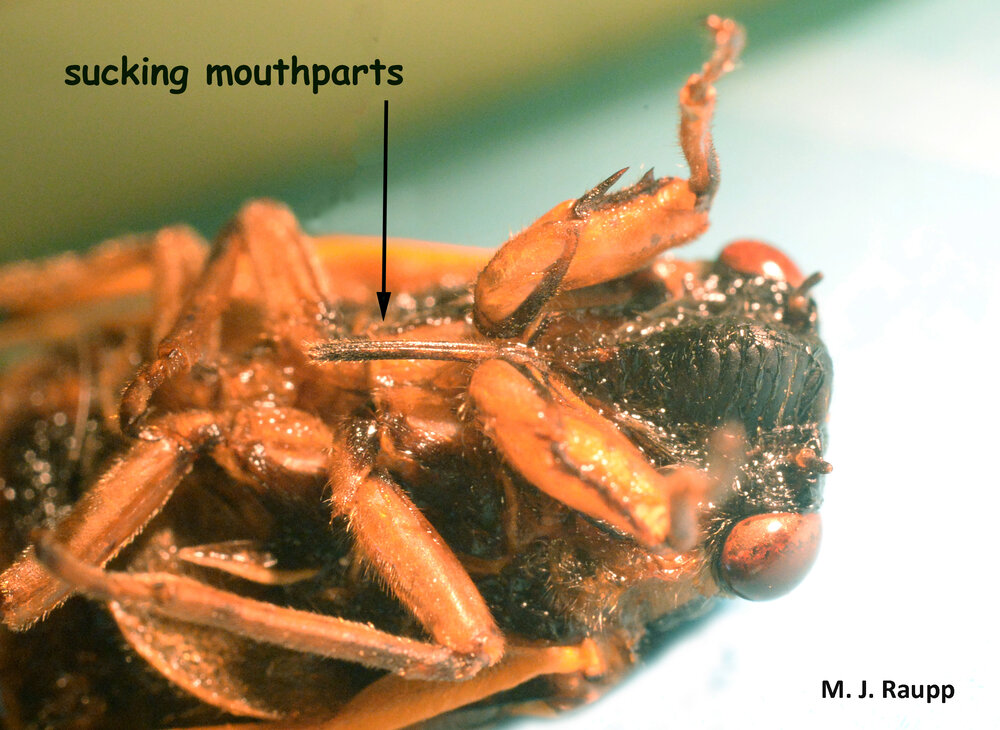

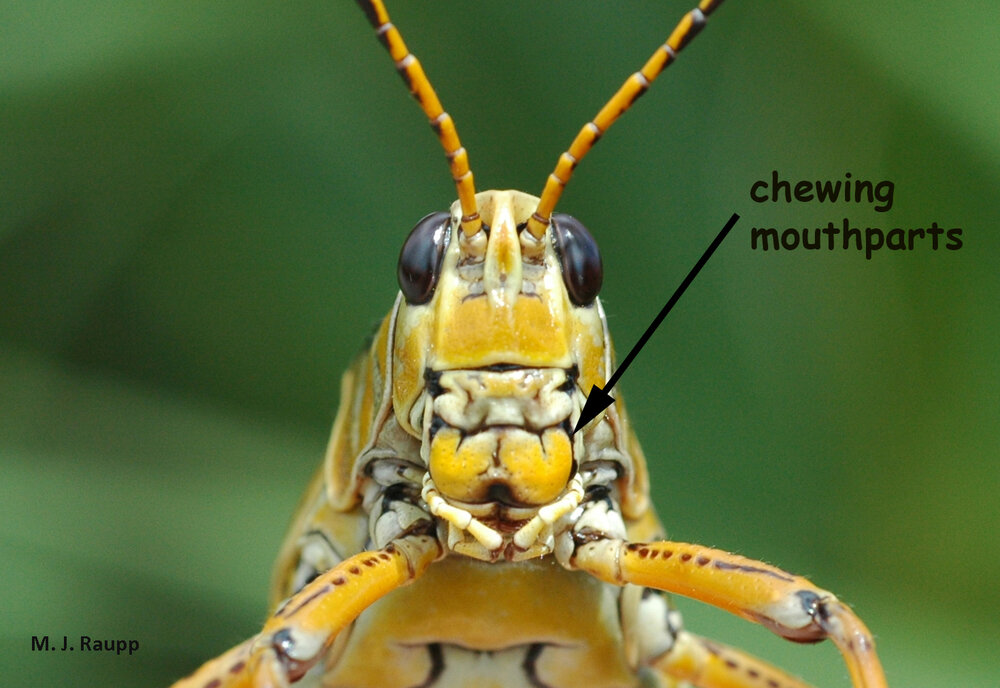

In a previous episode, we described the bizarre strategy called predator satiation used by periodical cicadas to overwhelm hordes of hungry predators intent on filling their bellies with these nutritious insects. The cicada’s long life span may also enable periodical cicadas to elude short-lived predators such as birds and small mammals that simply track cicadas through time. Who can wait 13 or 17 years for their next meal? But one patient nemesis of periodical cicadas has evolved a diabolical plan for making the most of the cicada bounty. In the soil beneath trees where cicada nymphs spend their youth sipping sap, resting spores of the fungal pathogen Massospora cicadina lay in wait for 13 or 17 years. During April and May as cicada nymphs escape from the earth, spores of Massospora adhere to the exoskeletons of nymphs. Compounds on the surface of the cicada send a signal to the spores that dinner is served and it is time to germinate. Like an invading army, the fungus penetrates the skin of the cicada and multiplies, turning the cicada into a fungus garden. In a short suspense, the infection turns the abdomen of the cicada into a buff-colored mass of fungus. At this stage of their life cycle, tens of thousands of newly molted adult cicadas populate the landscape to begin the courtship rituals. The infection sterilizes both male and female cicadas, but does nothing to quell the libido of the sex-crazed male cicada. Infected males continue to seek and attempt to mate with females despite their contagious infection. In a game of tit for tat, female cicadas infected with Massospora remain attractive to healthy males that soon become infected as they attempt to mate with females. At this point in time Massospora becomes a cicada STD and is transmitted from one cicada to another, thereby increasing its numbers each day. While the STD is strange enough, Massospora has one more trick to ensure maximum transmission of its spores. Recall from last week’s episode, that in the cicada mating game, after the male cicada puts on his best performance, the female signals her willingness to mate with an audible series of wing flicks. By a still not fully understood physiological mechanism, Massospora exerts mind control over an infected male cicada, causing him to mimic the female’s wing flick behavior. This results in horny male cicadas attempting to mate with Massospora infected males, further spreading the fungus through the cicadas’ populations.

Early in the Massospora infection cycle males and females with distended, distorted abdomens appear. Soon, fungal spore masses replace terminal abdominal segments. Sterile infected cicadas walk around and fly about, attempting to mate with uninfected cicadas and spewing spores into the environment while infecting their brood mates. Nearby, a healthy male cicada becomes entangled with an infected cicada in a bizarre pas de deux. In a strange twist of mind control, Massospora causes male cicadas to mimic the female’s wing-flick behavior, her coy signal of willingness to mate. Watch as a male uses his courtship call and attempts to woo a fungus-infected cicada that had just flicked its wings. His overactive libido will likely end in a lethal infection,n further spreading Massospora through cicada land. Videos by Michael Raupp and Paula Shrewsbury

Cicadas wandering about with hollow abdomens missing abdominal segments are hallmarks of the fungal infection.

A recent discovery of psychoactive compounds produced by Massospora suggests that these neuromodulators may play a role in altering the male’s behavior, contributing to the active transmission of the fungus by the cicada. Infected cicadas are flight capable and their peregrinations carry the fungus to new habitats as cicadas fly about. In low density populations of cicadas, mortality rates caused by Massospora range < 5% to ~ 25%. A second, more sinister wave of infection follows the first. In this stage, fungus-laden abdomens of infected cicadas and dying infected cicadas inoculate the soil with the resting spores of Massospora. While the loss of an abdomen spells instant death for a human, this is not the case for a cicada. Sensory and integrative neurological functions in the head and locomotory functions of flight and walking directed by the thorax remain intact despite the loss of the abdomen. As the season of the cicada progresses throughout cicada land, keep an eye out for male and female Massospora victims as they walk about missing their abdomen, macabre reminders of a very clever fungus.

Acknowledgements

The wonderful articles “A specialized fungal parasite (Massospora cicadina) hijacks the sexual signals of periodical cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae: Magicicada) by John R. Cooley, David C. Marshall, and Kathy B. R. Hill, “The ecology, behavior, and evolution of periodical cicadas” by K. S. Williams and C. Simon, and “Behavioral betrayal: How select fungal parasites enlist living insects to do their bidding” by Brian Lovett, Angie Macias, Jason E. Stajich, John Cooley, Jørgen Eilenberg, Henrik H. de Fine Licht, and Matt T. Kasson where used to prepare this episode.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week