Dashing through the snow: Snow scorpionflies, Boreus sp.

Among frosty fronds, a scorpionfly gazes on a frozen landscape. Does she await her mate or ponder her next bite of moss?

Last week parts of the east coast were treated to their first real taste of wintry weather in the form of bone chilling temperatures, freezing rain, and snow. As we wind-down what has been a spectacular year for many of our six-legged friends, is it time to bid farewell to insects outdoors? Well, not exactly. You see, many tiny and not so tiny arthropods have adapted to a hibernal lifestyle and can be visited even on days when mammals are snoozing snugly in a cave or curled up in front of a fire sipping hot chocolate and reading a book. This week we visit one such character enjoying its day in the winter sun.

Neither snow, nor ice, nor freezing temperatures can stop a female scorpionfly from scaling a miniature glacier to reach a scrumptious patch of moss.

Carol Of The Bells by Audionautix is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Artist: http://audionautix.com/

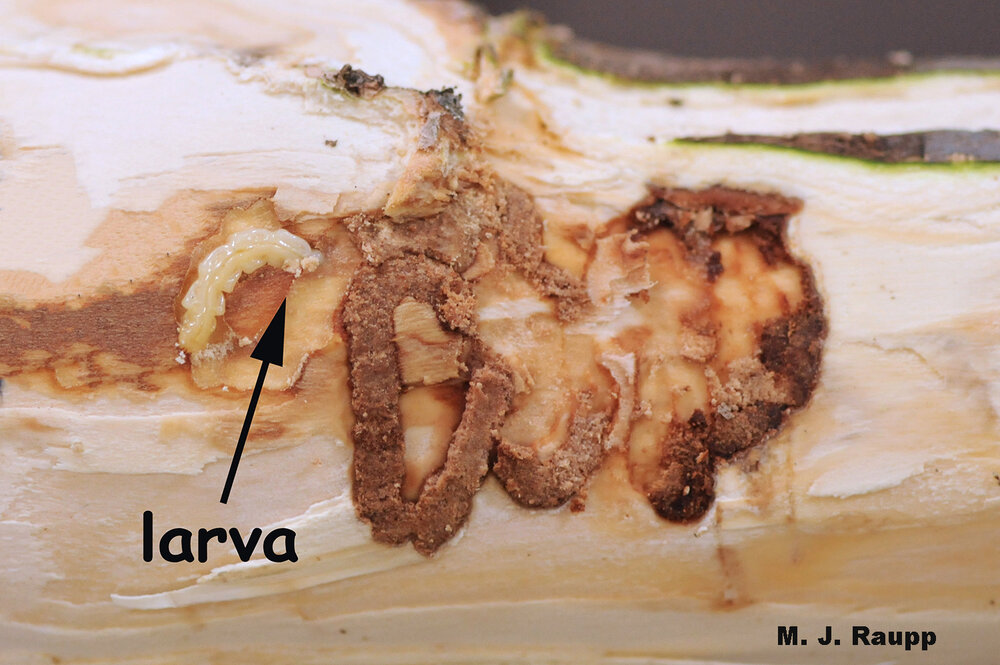

In a patch of moss near the banks of an icy stream, one of my colleagues discovered snow scorpionflies, one of the rarest insects we will meet in Bug of the Week. Snow scorpionflies are not scorpions, nor are they flies. They belong to a small order of insects known as Mecoptera. The “scorpion” moniker stems from the fact that some species of male scorpion flies have unusually large and upward curving genitalia that resemble the stinger of a scorpion. The “fly” part of the name comes from the fact that many species of Mecoptera have wings and can, well, fly. The tiny snow scorpionflies featured in this bug of the week do, in fact, lack functional wings, and cannot fly. Most species of snow scorpionflies are boreal and live in chilly places such as Alaska and Canada or occupy high elevations in mountains. They are active during the colder months of the year and can be seen with some regularity hopping about even on very frosty days. However, in Maryland snow scorpionflies can be found in the dead of winter on snow, ice, or on mosses and liverworts that serve as food for both adults and their larvae.

Chilly feet don’t cool the romance between winter-loving scorpionflies.

In one of the more curious mating rituals in the insect world, the male scorpionfly couples with the female, grasps her, and places her on his back for a nuptial ride. One has to wonder if this piggyback routine is just for fun or more likely a way to limit access to her by interloping suitors. If you hope to glimpse these fascinating creatures, dress warmly and bring along your magnifying glass. Snow scorpionflies are tiny insects, usually five or fewer millimeters in length. In a strange and still mysterious twist of evolution, snow scorpionflies are believed to be the ancient relatives of one of our more well known and itchy insect friends, the fleas.

Bug of the Week wishes all of you a Happy Holiday and a joyous New Year.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Chris Taylor, Tom Pike, and Jeff Shultz for sharing his snow scorpionflies for this Bug of the Week. The wonderful reference “Scorpionflies, hangingflies, and other Mecoptera” by G. W. Byers was consulted in preparation of this episode.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week