Winter mild or wild? Ask the banded woolly bear, Pyrrharctia isabella

How do woolly bear caterpillars predict winter weather and survive winter’s chill?

The banded woolly bear turns into the pretty Isabella tiger moth.

By virtue of the intimate relationship between weather and insect activity, folklore abounds about the ability of insects to predict meteorological events – when hornets build their nests high, a cold winter is on the way, when ants construct tall mounds, heavy rains are just around the corner, stuff like that. An annual preoccupation for many naturalists is taking a guess at what Old Man Winter has in store for us in the upcoming months. Fact-packed sources like NOAA predict “above normal” temperatures for the mid-Atlantic region and the tried and true Old Farmer’s Almanac predicts a “Season of Shivers” with “positively bone-chilling, below-average temperatures across most of the United States”. Entomologists know the consummate soothsayer of upcoming winter weather is the banded woolly bear caterpillar, the larval stage of the Isabella tiger moth.

Exactly when and where the prognosticative abilities of woolly bears were discovered remains shrouded in mystery. However, Dr. Charles Howard Curran, an assistant curator at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City from 1947 until his retirement in 1960, popularized the forecasting skills of woolly bears. Dr. Curran made annual pilgrimages to nearby Bear Mountain Park each year between 1948 and 1956 to observe woolly bears and gather data on their color patterns. He measured the width of colored hair bands on the body of woolly bear caterpillars to forecast the severity of the upcoming winter. His observations gained notoriety when published in the New York Herald Tribune. He concluded that a wide orange or brown band in the middle of the caterpillar bordered by black bands at head and tail forecast a mild winter. Conversely, wider black segments with a narrow band of brown or orange in between forewarned of a long, severe winter. Several other entomological experts around the country have used various clues garnered from the woolly bears to predict the winter weather. Claims of 70-80% accuracy are not uncommon.

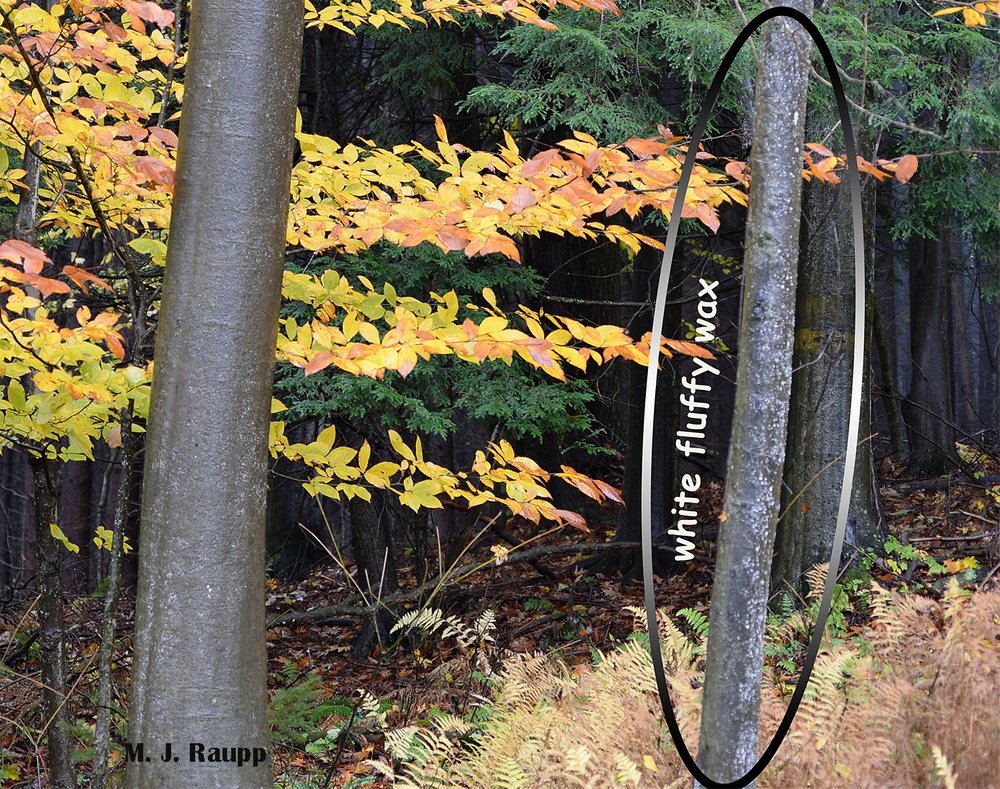

A woolly bear caterpillar bedecked with just a few black segments front and back, and many segments in the middle festooned with orange or brown is thought to be the harbinger of a mild winter. Conversely, a woolly bear with a narrow band of orange or brown sandwiched between large bands of black at head and tail signals a severe winter ahead. Having encountered representatives of both camps recently, perhaps the woolly bears are predicting a relatively mild winter with intermittent periods of severe cold. Clever meteorologists are these woolly bears.

When threatened, the woolly bear caterpillar curls into ball with a phalanx of stout, outward-facing spines which send a strong warning to would-be predators and bug geeks.

I usually think of caterpillars as rather delicate creatures and wonder why woolly bears don’t spend winter in a more durable stage like an egg or pupa, as do many other moths and butterflies. Even in Maryland polar vortices sometimes visit and drop temperatures below zero. A fascinating study by Jack Layne and his colleagues revealed that woolly bear caterpillars survive winter’s cold through a process called supercooling. As temperatures drop in autumn and early winter, woolly bears and many other species of insects produce cryoprotectants, antifreeze-like compounds including glycerol and sorbitol, that prevent the formation of lethal ice crystals in their bodies. This brew of Mother Nature’s antifreeze allows caterpillars to survive even when ambient temperatures dip well below freezing. The ability to shrug off cold enables the partially grown woolly bear caterpillar to overwinter as a larva, and with the return of warm temperatures in spring and arrival of fresh leaves, the caterpillars resume feeding for a while before spinning a cocoon and completing the transformation to an adult moth.

Imagine my delight when on a recent trip to the field, I discovered a banded woolly bear caterpillar with virtually no black bands on its body save for a few dark segments near the head. What with wildly inflating fuel prices and my ancient furnace gulping gallons of fuel oil, the prospect of lower oil bills loomed large. These hopes were thoroughly dashed a week later when I spotted a banded woolly bear with but a few orange colored segments in the middle and wide black bands at head and tail sanctioning the Farmer’s Almanac forecast of severe weather ahead. Has discord so rampant in the world of humans spread to the realm of woolly bears as well? Let’s hope not. Perhaps these seemingly disparate meteorological predictions are reconciled like this: “Woolly bears are predicting a relatively mild winter with intermittent periods of severe cold.” Clever meteorologists are these woolly bears.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Sheri, Finn, and Iggy for inspiring this episode and Karin Burghardt for providing images and identifying featured caterpillars. David Wagner’s remarkable book, “Caterpillars of Eastern North America”, was used to prepare this story, as was the interesting article “Cold Hardiness of the Woolly Bear Caterpillar (Pyrrharctia isabella Lepidoptera: Arctiidae)” by Jack R. Layne, Jr., Christine L. Edgar, and Rebecca E. Medwith.

This post appeared first on Bug of the Week